Consequentialism became the most popular approach to ethics following the Age of Enlightenment. Writers in the late 18th and early 19th century saw how strict, rule-based, duty-bound theories of ethics resulted in contradictory and often destructive behavior. After Napoleon’s wars and the bloody French Revolution that followed, philosophers wondered how our individual decisions impact the communities we live in. As the Industrial Revolution began, politicians and scholars alike wondered: what responsibilities do we have to society?

What is consequentialism?

It’s right there in the title: consequentialism is about consequences. The view of consequentialists is that what is and is not ethical depends only on the outcome of our decisions.

It’s helpful to compare consequentialism to deontology, which we covered in a previous essay. Deontology says that there is a logically consistent set of rules that can determine whether some act is ethical or not. Consequentialism says “it depends.” A rule that looks ethical in one case might result in unethical outcomes in another case. Consequentialism is based on an intuition: the best action now is whatever makes the world best in the future.

Many consequentialists believe that the best-ness of the future can be measured and counted. They call this best-ness “utility,” and by extension they are called utilitarians. In their view, comparing the utility of two decisions is the way to identify the right one.

A brief history of consequentialism

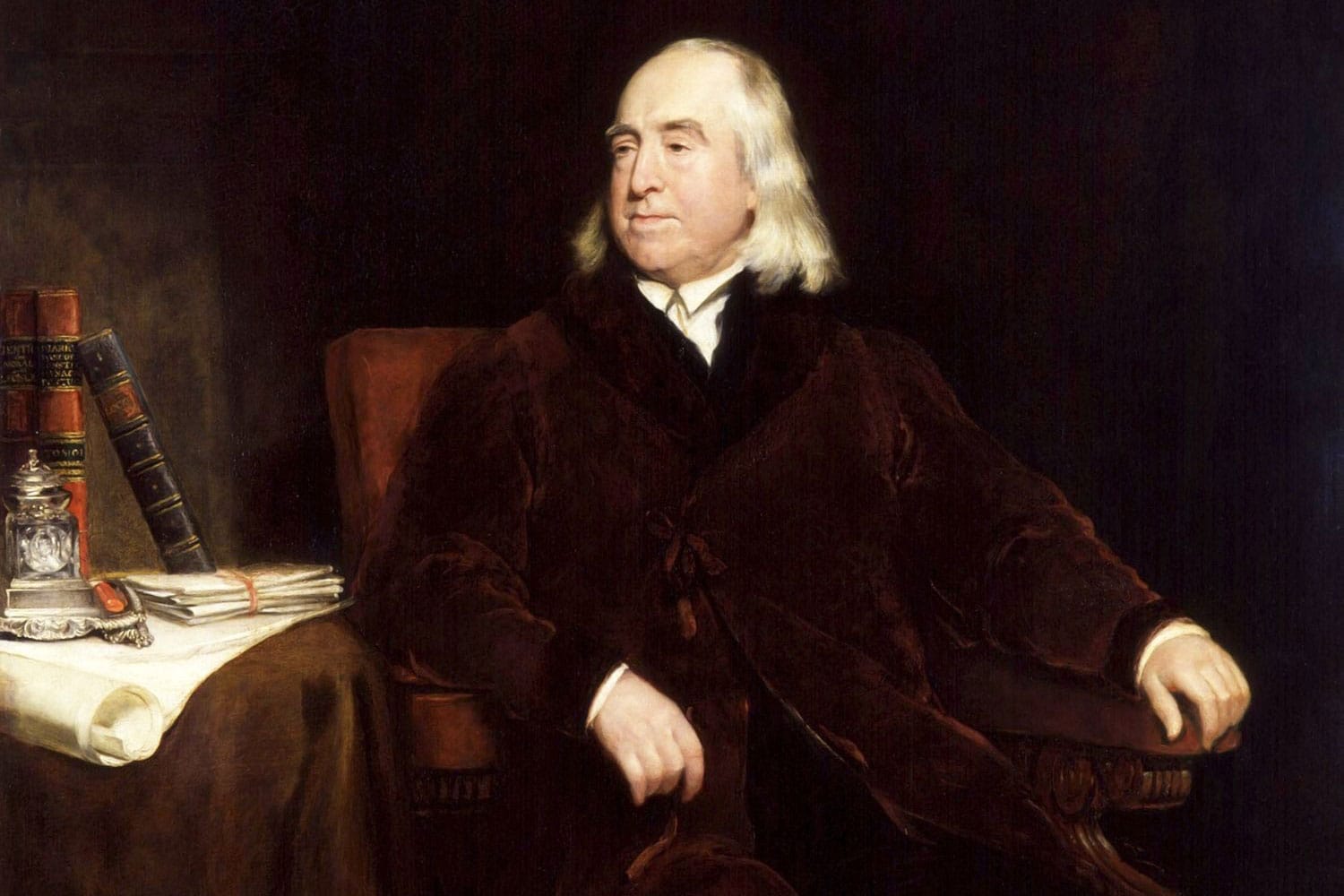

Jeremy Bentham is generally considered to be one of the founders of consequentialism and utilitarianism. Born in England in 1748, Bentham grew up similarly to Immanuel Kant; he was put in a series of strict schools and instructed mostly in classics and religion. This upbringing bred a dislike of the Anglican Church and a love for challenging norms and establishments.

After a false start as a lawyer, Bentham began his career in 1776 by writing anonymous pieces criticizing the English legal system. In A Fragment on Government, he wrote a short summary of utilitarianism: its “fundamental axiom” is that “it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong,” and “the obligation to minister to general happiness, was an obligation paramount to and inclusive of every other.”1 The happiness of others is the most important measure of right and wrong.

Bentham’s works were hugely influential. He knew this. In a dream, he imagined himself as “a founder of a sect; of course a personage of great sanctity and importance. It was called the sect of the utilitarians.”2 One of his most famous apostles was John Stuart Mill, born in 1806.

Mill took up the mantle of consequentialism. He wrote the book on utilitarianism, Utilitarianism, in 1863. In it, he clarified and defended many of Bentham’s ideas. “Happiness,” he wrote, “is the sole end of human action, and the promotion of it the test by which to judge of all human conduct.”3

Mill’s writings on social justice, economics, and government were powerful influences during a time of upheaval in England and abroad.

How do you measure consequences?

In considering our actions, it can be hard to add up the consequences. How much does inventing a cure for cancer count, compared to returning a stranger’s wallet? What if that stranger is inspired by your act of kindness, dedicates their life to bettering the world, and then invents a cure for cancer?

Consequentialists can be categorized according to how they handle a few high-level tensions:

- What is good? Some consequentialists like to keep things simple: called hedonists, they claim that only pain or pleasure matter when tabulating outcomes. Other philosophers believe that pain and pleasure aren’t everything: “Moore’s ideal utilitarianism, for example, takes into account the values of beauty and truth (or knowledge) in addition to pleasure (Moore 1903, 83–85, 194; 1912). Other consequentialists add the intrinsic values of friendship or love, freedom or ability, justice or fairness, desert, life, virtue, and so on.” 4

- Do intentions matter? Let’s go back to returning a stranger’s wallet. If the stranger goes on to do great things, can you take credit for those great things? You didn’t intend to contribute to cancer research when you decided to return the wallet. “Actual” consequentialists say that the actual outcomes of your actions are all that matter, while “foreseeable” consequentialists take your intentions into account.

- Who decides? Classic consequentialists like Bentham and Mill believed that the relative goodness or badness of an outcome shouldn’t depend on your perspective. Moral relativists argue that people have vastly different cultures, communities, and beliefs, resulting in vastly different conclusions about consequences.

These basic questions result in disagreements between consequentialists. But generally speaking, consequentialism has endured as an intuitive and useful approach to morals. Most legal systems today are based in consequentialism; it’s illegal to break the speed limit, whether you intended to or not. The severity of a criminal’s punishment is meant to be proportional to the consequences of their crime. In determining guilt, we look at evidence that connects actions to outcomes.

How to apply consequentialism to design

Consequentialism can be much easier to wield on a day-to-day basis than deontology or virtue ethics. Try it out: next time you’re designing anything, think ahead to the moment a user comes into contact with your work. What happens? Is the result good or bad for the user?

Of course, there’s much more nuance to consequentialism once you start to think about the impact to all users, and even more when you consider all decisions in aggregate. Fortunately, there are tools you can use to break the problem down into more manageable pieces; one particularly helpful framework is called the double bottom line.

The double bottom line

Business is about one thing: profit. Yield. The bottom line. The phrase is a reference to the final row in financial tables, summing the gains and losses to a single figure. The number goes up in good years, down in bad years. It gets reported by Bloomberg and the Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal. It’s shorthand for brevity. “Tell me, doc, what’s the bottom line?”

In the late 20th century, stakeholders realized that there was more to business than profit. The term “double bottom line” began to appear as early as 1996 in books like New Social Entrepreneurs by Jed Emerson and Fay Twersky. The second bottom line represents the social impact of a business — profit alone is, at best, meaningless; worse, it can be baffling or misinforming.

In a 2004 article in Business Ethics Quarterly, Wayne Norman and Chris MacDonald provided a list of metrics that might add up to the second bottom line 5:

Diversity

- Existence of equal opportunity policies or programmes;

- Percentage of senior executives who are women;

- Percentage of staff who are members of visible minorities;

- Percentage of staff with disabilities.

Unions / Industrial Relations

- Percentage of employees represented by independent trade union organizations or other bona fide employee representatives;

- Percentage of employees covered by collective bargaining agreements;

- Number of grievances from unionized employees.

Health and Safety

- Evidence of substantial compliance with International Labor Organization Guidelines for Occupational Health Management Systems;

- Number of workplace deaths per year;

- Existence of well-being programmes to encourage employees to adopt healthy lifestyles.

- Percentage of employees surveyed who agree that their workplace is safe6 The idea is that, by measuring and reporting on these numbers, businesses are made aware of the consequences of workplace policies. By extension, you can measure your design’s second bottom line by identifying metrics that reflect the social impact of your work.

Erika Hall refined this approach in “Thinking in Triplicate.” Her writing is some of my favorite when it comes to ethics; I urge you to read the whole article. One of the most memorable lines comes at the beginning:

A good user experience is only as good as the action it enables. Designing a system that makes it easy to do bad things is bad.7

Hall links to a New York Times article on Facebook’s advertising platform. The platform’s features allowed advertisers to target ads in a way that excluded women and minorities — a violation of the Fair Housing Act.8 Facebook’s intentions were likely not malicious: it allowed advertisers to “target who sees [ads] by selecting from preset lists of demographics, likes, behaviors and interests, while excluding others.” “Pet food companies, for example, could send their ads specifically to people who had indicated an interest in dogs, while excluding cat and bird fanciers.”

But the consequences of this design choice were dire. In addition to enabling housing discrimination, Facebook’s ad targeting has been used to exclude older candidates from job searches;9 divide political messaging to maximize anger;10 and single out vulnerable teens.11

Facebook isn’t the only platform that could benefit from understanding the social impact of its products. Every social media app, enterprise SaaS application, cloud technology provider, and e-commerce platform should be measuring and reporting its double bottom line.

Problems with consequentialism

Consequentialism puts a heavy burden on anyone who thinks hard enough about their actions. For example, I’m writing this essay on a Sunday afternoon. I’ve been at it for a few hours. Surely, I could have had a much more positive impact with those few hours than sitting at my computer: I could have volunteered at a local food bank. I could have donated some money to a charity. I could have taken some clothes to Goodwill. Was it immoral for me to spend the time writing?

Another criticism of consequentialism — really, a criticism of all the theories we’ve explored so far — is that it puts too much emphasis on individuals to make positive changes to the world around them. Historically, privileged people — wealthy, land-owning, white, male — have had more power than others. According to most traditional ethical theories, these privileged people have a greater part to play in ethics and morality than people who are oppressed, excluded, and minimized.

In the late 21st century, writers began to explore new ways of framing ethics that considered the relationship between powerful and powerless people. We’ll explore those theories, called care ethics, in the next installment.

Conclusion

Consequences matter. That’s the most intuitive way to think about ethics; it’s amazing that it took us thousands of years to come to the conclusions of Bentham and Mill. Today, consequentialism remains just as popular as it was at the dawn of the industrial era.

But designers aren’t encouraged to consider the consequences of their own decisions. Market incentives like profit, return on investment, and stakeholder value muddy our understanding of the products we create. We can avoid making things worse only by measuring and reporting the ethical outcomes and social impact of design — the double bottom line.

It’s up to us to create things that increase the well-being of our friends, neighbors, family, community, country, and planet.

Jeremy Bentham, The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham: A Comment on the Commentaries and A Fragment on Government, edited by J. H. Burns and H. L. A. Hart. (Oxford University Press, 1977). ↩︎

James E. Crimmins, Secular Utilitarianism: Social Science and the Critique of Religion in the Thought of Jeremy Bentham (Oxford University Press, 1990). ↩︎

John Stuart Mill. Utilitarianism (Boston, MA: IndyPublish, 2005). ↩︎

Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, “Consequentialism,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, summer 2019 (Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2019). ↩︎

Astute readers will notice that the original article discussed a triple bottom line, not a double bottom line. The triple-bottom-line framework, designed in 1994 by John Elkington, included sustainability and environmental impact as a third bottom line. However, in 2018, Elkington revisited his original ideas, proposing a “strategic recall,” lamenting that the triple bottom line framework didn’t catalyze the type of change he intended. See Elkington’s article “25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It.” at Harvard Business Review, published June 25, 2018: https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it ↩︎

Wayne Norman and Chris MacDonald, “Getting to the Bottom of ‘Triple Bottom Line,’” Business Ethics Quarterly 14, no. 2 (April 2004): 243–62. ↩︎

Erika Hall, “Thinking in Triplicate,” Mule Design Studio, Medium.com, published July 16, 2018: https://medium.com/mule-design/a-three-part-plan-to-save-the-world-98653a20a12f. ↩︎

Charles V. Bagli, “Facebook Vowed to End Discriminatory Housing Ads. Suit Says It Didn’t.” The New York Times, published March 27, 2018: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/27/nyregion/facebook-housing-ads-discrimination-lawsuit.html. ↩︎

Julia Angwin, Noam Scheiber, and Ariana Tobin, “Facebook Job Ads Raise Concerns About Age Discrimination,” The New York Times, published December 20, 2017: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/20/business/facebook-job-ads.html. ↩︎

Dan Keating, Kevin Schaul, and Leslie Shapiro, “The Facebook ads Russians targeted at different groups,” The Washington Post, published November 1, 2017: https://washingtonpost.com/graphics/2017/business/russian-ads-facebook-targeting/. ↩︎

Sam Levin, “Facebook told advertisers it can identify teens feeling ‘insecure’ and ‘worthless’,” The Guardian, published May 1, 2017: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/01/facebook-advertising-data-insecure-teens. ↩︎