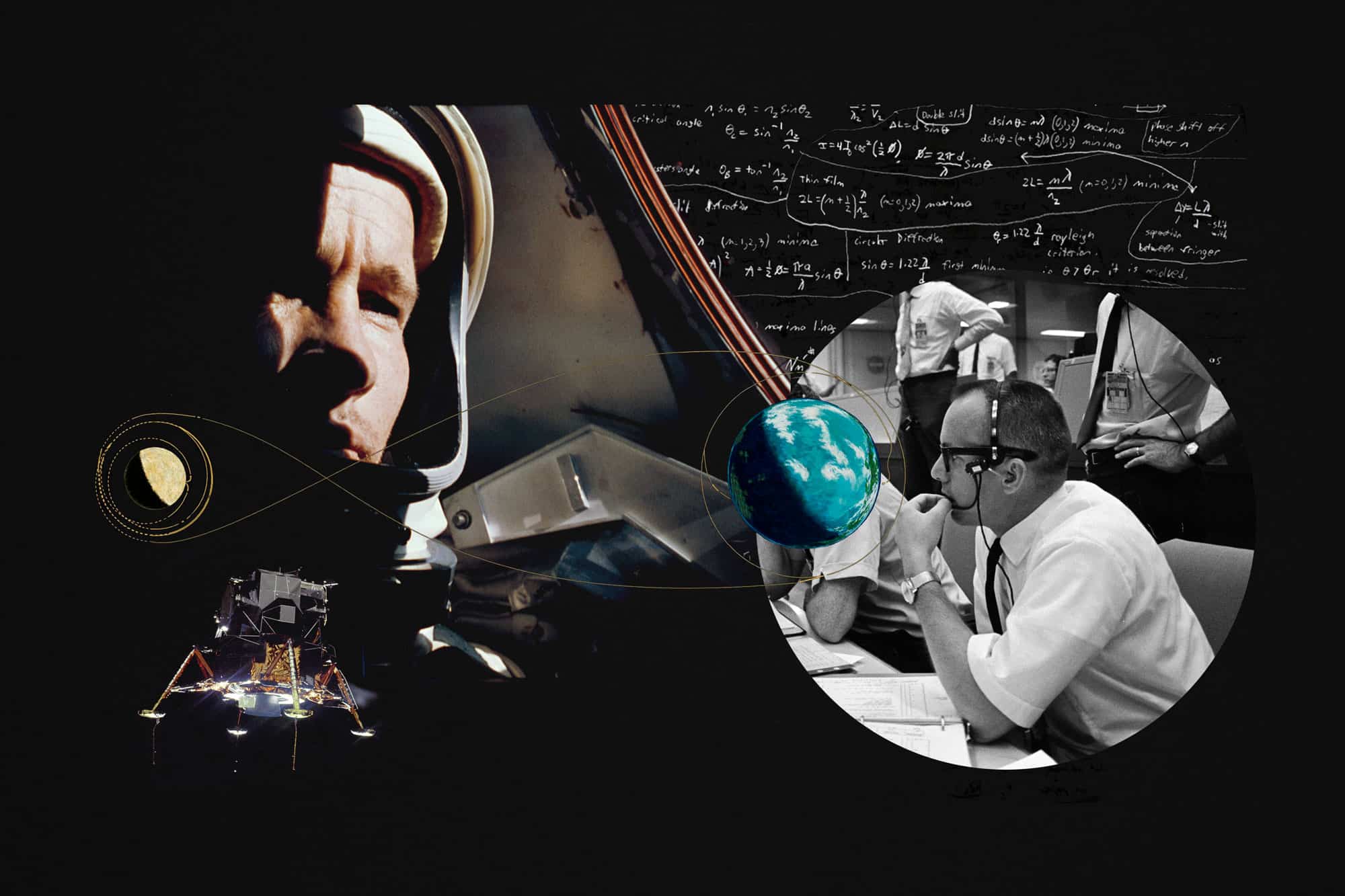

13 minutes from landing the Eagle on the surface of the moon, Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong had a problem. Their guidance computer was showing a cryptic alarm, flashing the number 1202. With the mission (and their lives) in danger, the astronauts had to make a decision: continue or abort?

6 months of intense training, billions of dollars in taxpayer money, and the greatest technological innovations in history all led up to this moment. None of that mattered now. In this moment, the difference between success and failure was a simple rule of management: make decisions at the lowest level possible.

The chain of command

Neil Armstrong was the commander of Apollo 11, responsible for making decisions aboard the lunar lander. During the landing, He and Buzz Aldrin (who was piloting the lander) were in direct communication with the Capsule Communicator in Houston, Charles Duke. When the alarm appeared, Armstrong and Aldrin nervously called out to Duke1:

(06:38:30) Armstrong: It's a 1202.

(06:38:32) Aldrin: 1202.

(06:38:48) Armstrong: Give us a reading on the 1202 program alarm.

(06:38:53) Duke: Roger. We got - We're GO on that alarm

(06:38:59) Armstrong: Roger.

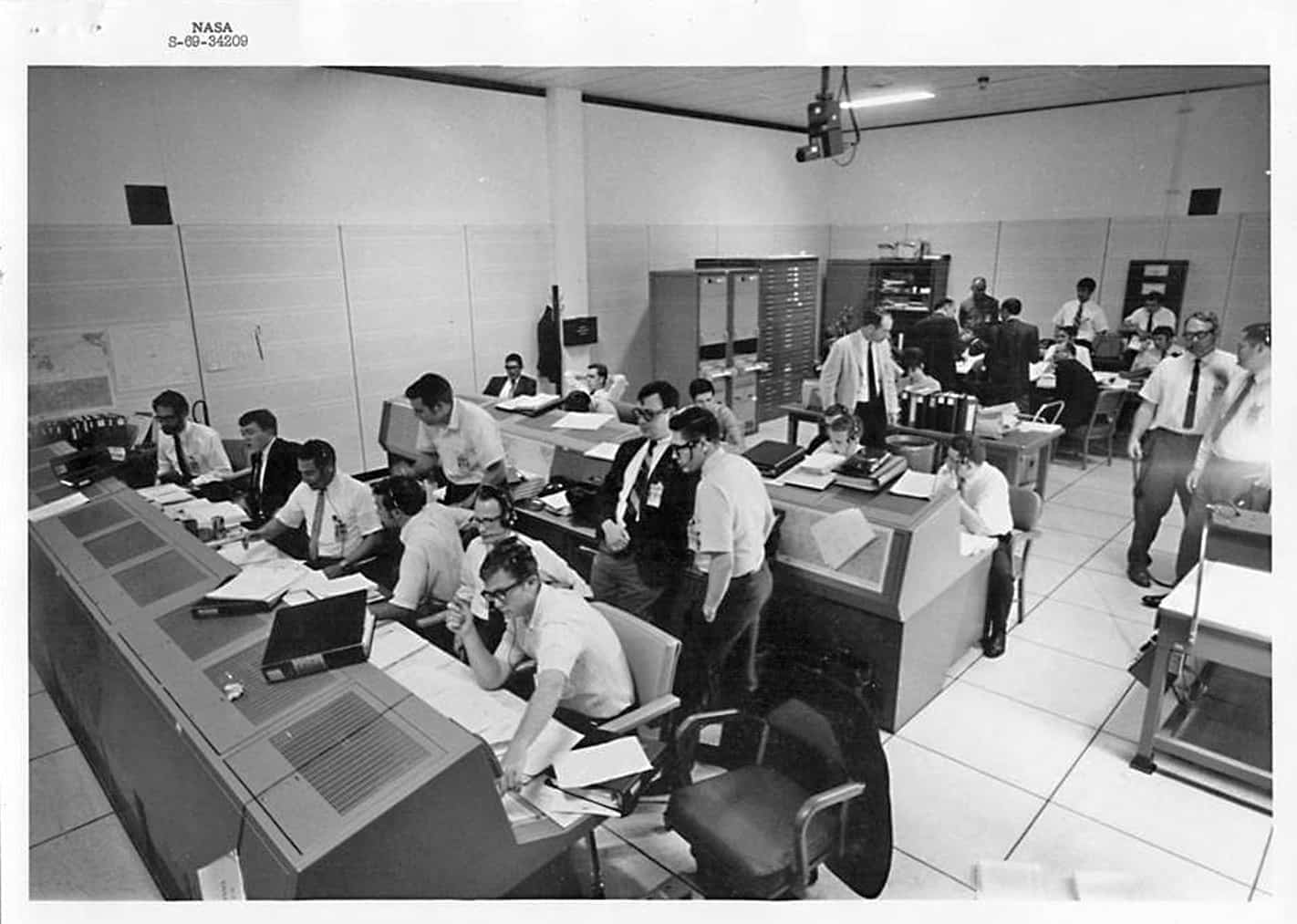

Duke’s call of “we’re go” was a blessing to continue with the mission. But Duke didn’t make that decision himself. Neither did the flight director for Apollo 11, Gene Krantz. Neither did Steve Bales, the man in the control room responsible for the guidance computer. The decision to either continue or abort passed quickly down the chain of command, from Duke to Krantz to Bales, and finally to Jack Garman, a 23-year-old NASA computer engineer.

Garman was the right person to make the call. During a simulation two weeks before the mission, Garman’s supervisor Steve Bales had run into a similar scenario: an unknown computer error during descent. But in this simulation, he called for the mission to be aborted. Bales describes the result:

At the debriefing, we got into a big argument. The simulation supervisor said ‘I don’t think you should have called that abort.’ … [Flight director Gene Krantz] came to me and said 'Steve, I want you to have a new mission ruleset that covers unexpected alarms.2

With so little time remaining until launch, Bales entrusted the task to Jack Garman. Garman studied every possible computer error and wrote a plan for handling each.

So as Eagle plummeted towards the moon, the 1202 error was relayed through mission control, from Duke to Krantz to Bales, and then on to Garman. He replied immediately:

“It’s an executive overflow, if it doesn’t happen again, we’re fine.”

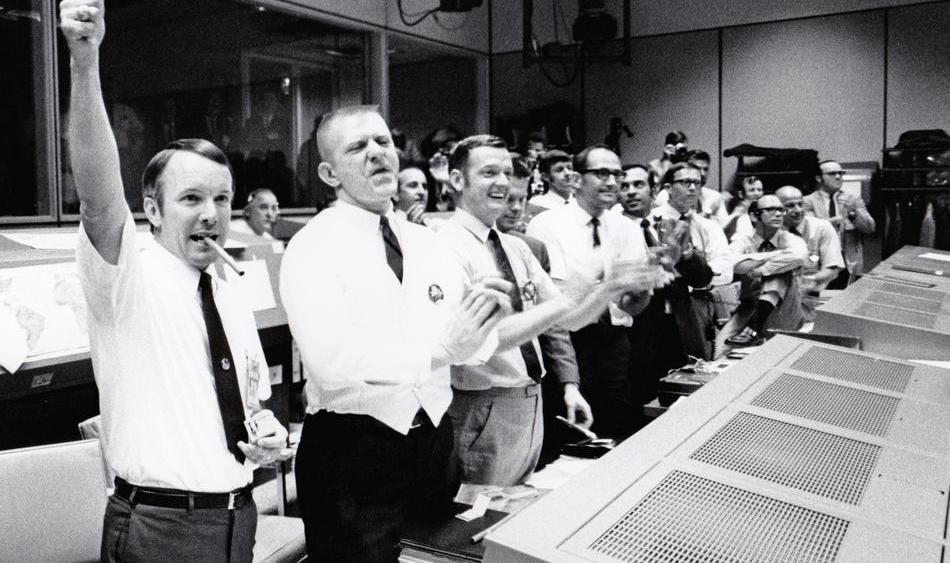

Back up the chain, “go” was echoed by Bales, Krantz, and finally Duke, telling the astronauts that they could safely continue their landing.

From the ground up

Five men could have made a decision faster than the time it took to reach Garman. Each of them, without thinking, passed their responsibility down the chain.

These decisions made the first moon landing possible. But to the people that made them, it was second nature. Guidance officer Steve Bales explained it this way:

“We didn’t make decisions at the highest level possible. We shoved them down to the lowest level. Now, the flight director, for instance, had to understand the inputs he was getting. But everyone had their piece of the pie, and we didn’t try to share it too much. We didn’t have time. Make the decisions at the lowest level, where people know what they’re doing and what they’re talking about, rather than elevating everything to the top. Let’s build this thing from the ground up.”

This style of decision-making is the complete opposite of management in modern organizations. In today’s companies, decisions are made at the highest level; by the board, the c-suite, senior vice presidents, etc. Leaders with great decision-making abilities are sought after. Entire classes at the most selective business schools are taught on how to make decisions.

But in 1969, the people in charge of Apollo 11 trusted a 23-year-old engineer in a back room of mission control to make one of the most consequential decisions of this decade-defining mission. And they did so in seconds, without deliberating or debating.

To the moon

Next time you’re faced with a decision, ask yourself: how can this decision be made on the lowest level? Have you given your team the authority to decide? If you haven’t, why not? If they’re not able to make good decisions, you’ve missed an opportunity to be a leader. Empower, enable, and entrust them. Take it from NASA: the ability to delegate quickly and decisively was the key to landing men on the moon.

Read the time stamps: this whole exchange happens in 43 seconds. This is even more impressive when you take into account the physical signal delay: messages take a little more than a second to go from the earth to the moon. ↩︎

From episode 2 of BBC’s 13 Minutes to the Moon, Kids in Control ↩︎