Virtue ethics was one of the earliest attempts at defining a language and a logic around ethics. The effort to identify and understand virtues began in Ancient Greece and continues to this day.

What is a virtue?

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines a virtue as “an excellent trait of character.”

It is a disposition, well entrenched in its possessor — something that, as we say, goes all the way down, unlike a habit such as being a tea-drinker — to notice, expect, value, feel, desire, choose, act, and react in certain characteristic ways.1

Leave it to philosophers to use tea-drinking as an example of a habit.

A virtue is a desirable personality trait. Kindness, fairness, patience, honesty, courage, and compassion are all examples of virtues.

Virtue ethics is the belief that well-being comes from having the right personality traits or dispositions.

Virtues are a very intuitive way to think about ethics. You probably feel some sense of right and wrong (unless you’re a psychopath). While we may disagree on the full list of virtues, we can agree that people with personality traits like kindness and compassion tend to improve the lives of others.

A brief history of virtue ethics

Our definition and understanding of virtue hasn’t changed much in the last 2,000 years. To understand what it means to be virtuous, we should start with Socrates.

Virtue comes up a handful of times in Plato’s account of Socrates’ trial. A notable moment occurs when Socrates responds to the accusation that he was corrupting the youth of Athens:

I do nothing but go about persuading you all, old and young alike, not to take thought for your persons and your properties, but first and chiefly to care about the greatest improvement of the soul. I tell you that virtue is not given by money, but that from virtue come money and every other good of man, public as well as private. This is my teaching, and if this is the doctrine which corrupts the youth, my influence is ruinous indeed.2

To Socrates, virtue was skill in the art of living. The making of character. Wisdom. You can’t buy virtue; you earn it through self-examination. And living virtuously would lead to wealth, material or otherwise.

Other philosophers — like Plato — attempted to define virtue on their own terms. After Socrates’ death, Plato wrote the Republic, the highlight of his long career as a scholar. In it, he discusses the deep, underlying meaning of ethics. What does it mean to live an ethical life? What is the point?

Plato, along with other early philosophers, used the word eudaimonia to refer to the result of living ethically. Eudaimonia is Greek; it’s typically translated as happiness, or well-being. But eudaimonia has the subtext of prosperity and a meaningful existence. Eudaimonia is the aim of all our thoughts and actions, and virtues like courage, piety, and temperance are the skills we need to achieve that aim.

But eudaimonia doesn’t come easy. To Plato, being truly virtuous required decades of studying, discussing, and practicing philosophy:

At the age of fifty those who have survived the tests and approved themselves altogether the best in every task and form of knowledge must be brought at last to the goal.3

A student of Plato’s named Aristotle disagreed. Instead of going to school for twenty years to learn how to be virtuous, Aristotle insisted that anyone can be virtuous simply by acting in the right way. Virtue, he said, is a frame of mind, a careful balance between extremes.

Aristotle’s books on ethics (the Nicomachean Ethics and the Eudemian Ethics) were the gold standard of moral philosophy from the time they were written in the fourth century BC all the way through the Middle Ages and well into the Renaissance. It wasn’t until the Enlightenment that philosophers took a critical look at virtue ethics and began to form alternative theories. We’ll get to those ideas in future essays.

How to apply virtue ethics

How do we achieve design eudaimonia? If ethical living requires skills — virtues — like kindness, fairness, patience, and honesty, then ethical design needs its own list of skills and practices. Ethical design needs design principles.

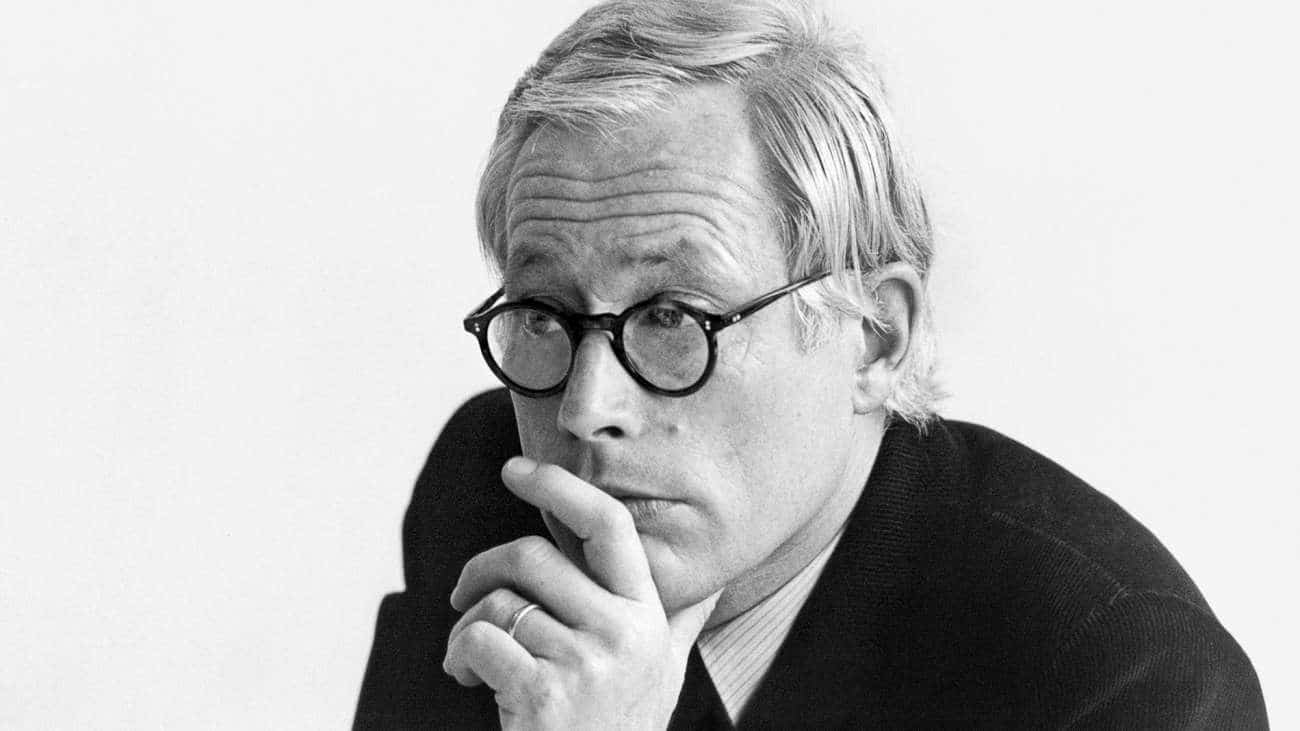

A design principle is a lot like a virtue: it’s a desirable attribute or disposition that leads a designer to make ethical design decisions. Designers have been writing down their principles as long as they have been designing. Dieter Rams’ “Ten principles for good design” is one of the most esteemed sets of design principles:

- Good design is innovative

- Good design makes a product useful

- Good design is aesthetic

- Good design makes a product understandable

- Good design is unobtrusive

- Good design is honest

- Good design is long-lasting

- Good design is thorough down to the last detail

- Good design is environmentally-friendly

- Good design is as little design as possible4

Rams wrote his principles in search of good design. He believes designers have a responsibility to produce good design, and that codified principles are the tools that will help them get there. In a 1976 speech, he outlined this conviction:

Ladies and gentlemen, design is a popular subject today. No wonder because, in the face of increasing competition, design is often the only product differentiation that is truly discernible to the buyer. I am convinced that a well-thought-out design is decisive to the quality of a product. A poorly-designed product is not only uglier than a well-designed one but it is of less value and use. Worst of all it might be intrusive….The introduction of good design is needed for a company to be successful. However, our definition of success may be different to yours. Striving for good design is of social importance as it means, amongst other things, absolutely avoiding waste. What is good design? Product design is the total configuration of a product: its form, colour, material and construction. The product must serve its intended purpose efficiently. A designer who wants to achieve good design must not regard himself as an artist who, according to taste and aesthetics, is merely dressing-up products with a last-minute garment. The designer must be the gestaltingenieur or creative engineer. They synthesise the completed product from the various elements that make up its design. Their work is largely rational, meaning that aesthetic decisions are justified by an understanding of the product’s purpose.5

Rams’ principles and beliefs were focused on producing physical goods, like radios, clocks, chairs, shelves, and calculators. A modern approach to ethical design needs principles for digital goods, too.

There are lots of great examples of ethical design principles for the digital era. Take Adam Scott’s “Principles of Ethical Web Development,” for example:

- Web applications should work for everyone

- Web applications should work everywhere

- Web applications should respect a user’s privacy and security

- Web developers should be considerate of their peers

What makes a good design principle?

While it’s possible to adopt other designers’ principles wholesale, I believe it’s more rewarding to write your own principles based on the work you do and the beliefs you have.

The design principles that work the best have the following traits:

Good design principles are memorable. You shouldn’t need to refer to a handbook to remember how to make ethical design choices. “Good design is as little design as possible” is the golden standard of a memorable design principle. Keep your principles to 10 words or less if possible.

Good design principles help you say no. Making ethical decisions requires prioritization and focus. Joshua Porter’s “One primary action per screen” principle is a great example: it gives us permission to make interactions obvious. Ethical design principles are as much about avoiding bad design as they are about producing good design.

Good design principles are specific to your own work. Lots of principles can be applied universally: to any design, by any designer, at any company. William Lidwell, Kritina Holden, and Jill Butler collected a whopping 125 of these common virtues in Universal Principles of Design. But writing your own principles is an opportunity to get specific. “Good design makes people’s lives better,” for example, is universal and hardly compelling. Yves Béhar, designer of often-lauded (and sometimes-maligned) products like Jawbone’s JAMBOX, the August Smart Lock, and Juicero’s $400 juice press, defined a much better version of this principle in his speech at the 2017 A/D/O festival. In his work with design and artificial intelligence, Béhar believes that “[good] design enhances human ability (without replacing the human).”6

Good design principles are applicable. Principles should give everyone on the team ideas of how to best practice them, and they shouldn’t be specific to one particular platform or discipline. “Solicit and respect user feedback” is a good example of a specific and applicable principle: whether you’re a product designer, project manager, front-end engineer, or sales rep, you can use this principle to be better connected to the impact of your work.

I’ve created a workshop you can run with your own team in one hour to write your own design principles. The instructions, along with more examples of good design principles, can be found on my website.

The problem with virtue ethics

If virtue ethics was perfect, this series would end here. Fortunately for me, there’s plenty more to write.

Philosophers in the 17th and 18th centuries were the first to identify problems with virtue ethics. Writers at the time looked for logical rules that could be applied to everyday life; Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica set off a cultural chain reaction with its clear demonstrations of physics and mathematics. Virtue ethics was too hazy for these Enlightenment thinkers.

Emmanuel Kant wrote a series of books starting in 1781 that called into question the validity of virtue ethics (and all other kinds of ethical philosophy). Virtues, he argued, can’t exist without a definition of good and evil; therefore, virtue ethics couldn’t stand on its own in providing rules for ethical behavior.

This critique is the clearest case for other kinds of ethical frameworks. Virtues are hard to define objectively, leaving room for paradoxes. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it:

What does virtue ethics have to say about dilemmas — cases in which, apparently, the requirements of different virtues conflict because they point in opposed directions? Charity prompts me to kill the person who would be better off dead, but justice forbids it. Honesty points to telling the hurtful truth, kindness and compassion to remaining silent or even lying. What shall I do?7

Kant and other philosophers during the Enlightenment tried to solve this ambiguity by creating a logical system of ethics. That system, called deontology, is the subject of our next essay.

Conclusion

Virtue ethics is not perfect. It can be a little fuzzy around the edges and requires you to make subjective judgements about what is and is not ethical. But the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and more contemporary philosophers like Michael Slote and Linda Zagzebski make for a great foundation.

Apply virtue ethics to design by crafting clear design principles and sharing them with your colleagues. Share your design principles with users. This keeps you accountable and builds trust. Discuss your principles with other designers and notice how they impact your work. These are key steps in building a conversation and a community around ethical design.

Join the mailing list

I'll send new posts to your inbox, along with links to related content and a song recommendation or two.

Rosalind Hursthouse and Glen Pettigrove, “Virtue Ethics,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, winter 2018, accessed February 3, 2020, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2018/entries/ethics-virtue/. ↩︎

Plato, Apology, translated by Benjamin Jowett, The Internet Classics Archive, Daniel C. Stevenson, Web Atomics, last accessed March 18, 2020: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/apology.html. ↩︎

Plato, Republic, edited and translated by Chris Emlyn-Jones and William Preddy (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2013), 540a. ↩︎

“Good design,” Vitsœ, accessed January 31, 2020, https://www.vitsoe.com/us/about/good-design. ↩︎

Dieter Rams, “Design by Vitsœ,” speech, Jack Lenor Larsen’s New York showroom, December 1976, last accessed March 19, 2020: https://www.vitsoe.com/files/assets/1000/17/VITSOE_Dieter_Rams_speech.pdf. ↩︎

Katharine Schwab, “10 Principles For Design In The Age Of AI,” Fast Company, published January 30, 2017, https://www.fastcompany.com/3067632/10-principles-for-design-in-the-age-of-ai. ↩︎

Hursthouse and Pettigrove, “Virtue Ethics.” ↩︎