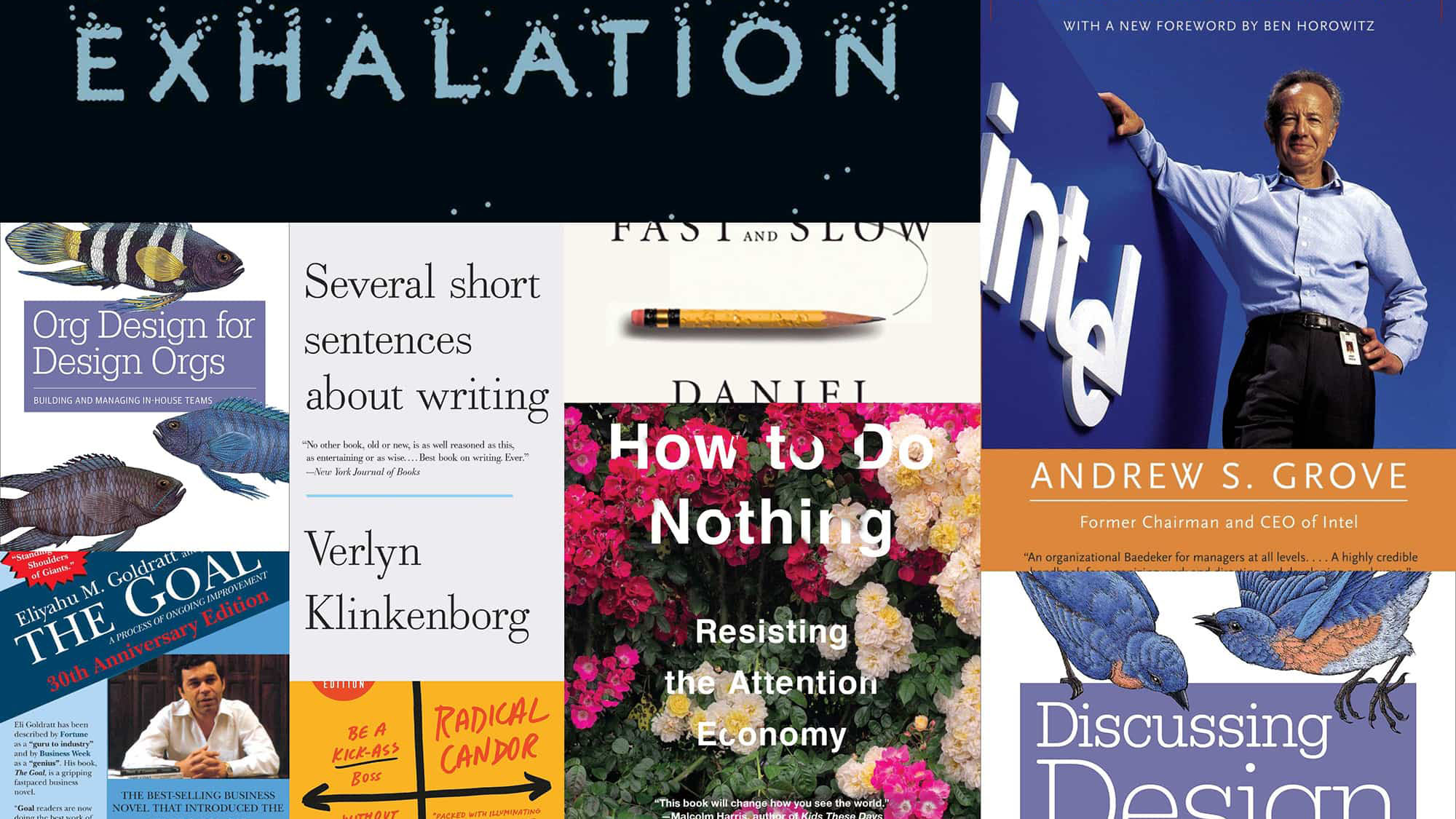

I read 25 books in 2019. That’s slightly more than last year, largely due to my discovery of the Kindle iOS and MacOS apps. The iOS can scroll continuously instead of flipping between discrete pages, which is ideal for the kind of non-fiction books I like to read. I still read on the Kindle itself, but that’s reserved for fiction and text I want to spend a little more time with.

I’ve also started sharing the my thoughts on these books when I finish them. You can see the full list over here.

The Fifth Season

by N.K. Jemisin

I picked up this book after seeing it won the Hugo Award in 2016. I love sci-fi, but had never really gotten into fantasy. This book promised to be a bridge between the two.

Jemisin builds a really fascinating world throughout the book. I enjoyed the way she avoids a lot of typical fantasy tropes, and her storytelling techniques work really well. However, the story suffers from a really common symptom of fantasy: the god-like character who is all powerful and can theoretically solve any crisis instantly without much trouble. This trope makes conflict much less dramatic, and ultimately takes the suspense out of the story.

Discussing Design

by Adam Connor and Aaron Irizarry

This book is a good collection of techniques to improve creative feedback. I’ve used a lot of them since reading it. My favorites:

- Critique to improve, not critique to approve. Remind stakeholders that their role isn’t to say ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ rather to give the designer actionable feedback for how to resolve any critical issues.

- Incremental vs. iterative - We often call work iterative when it’s actually incremental. That is: we don’t actually build a full usable version of a product, release it, and then progressively improve it. We start with an unusuable thing, and then slowly build it up until it’s in a largely finished state. Being able to make this distinction helps to set expectations and get the right kind of feedback.

- Six thinking hats - A good exercise to increase the quality and diversity of feedback is to assign ‘hats’ to participants which guide the kind of feedback they’re expected to give.

21 Lessons for the 21st Century

by Yuval Noah Harari

This one wasn’t as good as Sapiens, but was enjoyable nonetheless. Here’s one of my favorite passages:

Humans were always far better at inventing tools than using them wisely. It is easier to manipulate a river by building a dam than it is to predict all the complex consequences this will have for the wider ecological system. Similarly, it will be easier to redirect the flow of our minds than to divine what that will do to our personal psychology or to our social systems.

Leviathan Wakes

by James S. A. Corey

I tried to get Sasha to watch the TV show with me, but failed. So I started to read the book instead. I haven’t read any more of the ‘Expanse’ series, so it’s difficult to assess where the hype comes from. In part, I think it’s a blending of genres; there’s the typical science fiction bent, but there’s also a bit of noir, and a dash of post-apocalyptic distopia.

The whole book revolves around a mystery. Oddly, the mystery is solved at the end of the second act. This means the ending of the book feels like a foregone conclusion.

Endurance

by Alfred Lansing

Shackleton and his team went through an incredible ordeal. It’s impossible to imagine what it’s like to be completely stranded for three years in one of the harshest environments on earth, thousands of miles from the scraps of civilization. Not a single crew member died. How is this possible? Beyond that, the crew kept meticulous notes, even took photos of their ship being crushed by the ice.

An amazing fact: the expedition lasted the length of the first World War. The crew learned about it all retroactively. After all they went through, they returned to a completely different world.

Brave New Work

by Aaron Dignan

I got the chance to work with Aaron when he was leading a company called Undercurrent. His approach to work was so unique, and so clearly articulated, that I can still detect his impact on the folks he employed, 5 years after Undercurrent ceased to exist.

It was really nice to read all of Aaron’s advice summed up in a simple package. I use a lot of these techniques in my day-to-day: consent-driven decision making, inclusive meetings, and managing in the present. The schools of thought that created these concepts are also fascinating; if you get a chance, do some further reading based on the references in the book.

Exhalation

by Ted Chiang

Black Mirror x Borges — great short stories that explore some traditionally sci-fi concepts from more of a prodding, philosophical standpoint. The best part about Chiang’s stories are the feels … instead of being Borges-style think pieces, you get lots of emotional depth. Especially with the parrot.

Trillion Dollar Coach

by Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg, and Alan Eagle

Bill Campbell was an extraordinary coach. His experience coaching Columbia’s football team clearly influenced his approach to business. But this book isn’t really about Campbell’s coaching style. He cursed a lot, he gave good hugs, and he was a good listener: those are the memorable aspects of Campbell as a coach.

The book is really about the power of networks; Campbell had the good fortune of being connected to the right people at the beginning of Silicon Valley’s meteoric rise. His connections led to relationships with Steve Jobs, Larry Page, Sergey Brin, Eric Schmidt, Marissa Mayer, Sheryl Sandberg, and more. So, the takeaway: be a great coach, but make sure you have the right friends.

Midnight in Chernobyl

by Adam Higginbotham

Nuclear power is one of the cleanest sources of energy on earth. Its potential to save the planet from man-made climate change is enormous. That’s why the Chernobyl disaster is doubly tragic: first, the loss of life and catastrophic damage done to the Pripyat area were entirely preventable with better planning and communication. Second, the psychological impact of the disaster put a complete stop to the development of nuclear energy as a replacement for coal and oil.

Higginbotham does a really good job of illustrating the characters in the story of Chernobyl. Without these characterizations, it’d be difficult to relate to the Soviet planners that were at the center of the mistakes that led to the meltdown.

Einstein

by Walter Isaacson

In 1905 Einstein had never held an academic position. He published four papers that year: one on the Photoelectric effect (for which he won the Nobel Prize), one on Brownian motion which opened the door for the observation of the atom, one on special relativity which upendended our understanding of space and time, and one on the mass-energy equivalence which demonstrated the famous equation E = mc2.

It’s easy to get caught up in the mythos of Einstein, to think of him as the kind of genius that comes along once in a millenium. But the details of Isaacson’s biography paint a picture of the everyday life: family, work, the relatable struggle for recognition and self-fulfilment.

The Black Swan

by Nassim Taleb

I have a love-hate relationship with Taleb. His writing is dripping with ego. The book might as well be called I Was Right, since that’s the subject most of the time. But I have to hand it to Taleb, the way he tends to be right about things is interesting. I really resonate with the sentiment that people tend to take shortcuts and overlook data when the goal is certainty. Particularly this quote:

The more information you give someone, the more hypotheses they will formulate along the way, and the worse off they will be. They see more random noise and mistake it for information.

Thinking, Fast and Slow

by Daniel Kahneman ★

It’s hard to overstate the value of understanding bias. This book is a must-read: Kahneman has such a talent for unraveling the counter-intuitive nature of bias, heuristics, and the way people make decisions. His research with Amos Tversky (called prosepect theory) has influenced economics in ways I can’t understand, but the effect is recognizable when you book a hotel online (scarcity bias at play) or check out on Amazon.

The sections of the book on expert intuition were especially relevant at the time I read them, and helped me to write an essay called Intuition vs. Data.

How to Do Nothing

by Jenny Odell

This book is an expanded version of Odell’s talk/essay How to Do Nothing. It’s possible to get the gist of the book by reading the talk/essay, so start there if this concept is interesting to you. But there’s a few places in the book that Odell goes deep, and it’s worth a read.

One of my favorite threads throughout the book was the idea of active disengagement. That is, instead of running away from society and living in a mountain cabin off the grid, it is more revolutionary (and much harder) to resist in place. Doing nothing in the middle of the desert is very different than doing nothing in the middle of Times Square.

Pandemic

by A. G. Riddle

I picked this up looking for a break after reading a few heavy non-fiction titles. It delivered exactly that: an entertaining read with enough science to keep my brain busy. Specifically, the book includes some ideas from epidemiology, as its heroes have day jobs in agencies like the Centers for Disease Control. The conclusion of the book strays a little bit too far into Dan Brown conspiracy fodder, which means it was ultimately pretty forgettable.

Org Design for Design Orgs

by Peter Merholz and Kristin Skinner

I read this after my design team at Bitly was re-organized into a decentralized structure. I personally preferred being in a centralized org, so I thought I’d try and read a bit to understand why a decentralized org might make sense.

The biggest takeaway from this book is its articulation of the Centralized Partnership model (you can read the chapter on this model on O’Reilly’s Website). It’s exactly what I think most design orgs should be: centralized to provide designers with a sense of community and career development, but always partnered with other parts of the organization to deliver business outcomes. Essentially: there is no design in a vacuum.

Articulating Design Decisions

by Tom Greever

I’m constantly trying to improve the way I work with stakeholders. Feedback is the lifeblood of great design: when you see great design in the world, it’s a product of a group of people that agreed to deliver that design. Seldom is a single designer left alone to make all the decisions.

The author spends a lot of the book setting the scene for a meeting where design is critiqued and feedback is generated. I think that we’re going to quickly lose this model of design feedback. Agile working styles demand that designers deliver faster and faster, so asynchronous feedback will become the new norm. There are a few ideas from the book that can be taken into the new async world, but most will have to be left behind.

Children of Time

by Adrian Tchaikovksy

Children of Time is different. It’s definitely sci-fi. It has all the familiar space tropes: laser battles, light-speed travel, planetary crash landings. But its protagonists are spiders. That’s really the only way to begin to explain the different-ness of the book.

The spiders evolve from your garden variety (yow) spiders to extremely evolved intelligent tool-using spiders. Eventually the spiders develop the capacity to reach the upper limits of their atmosphere, building space networks of space stations out of silk. This description captures only one one-hundredth of the book’s plot arc, but I share it only to support my overall review, which is: don’t read this book if you don’t like spiders.

Competing Against Luck

by Clayton M. Christensen, Karen Dillon, Taddy Hall and David S. Duncan

This one’s a pretty standard business read; Christiansen (et al, there are lots of co-authors) describes the Jobs to be Done framework, examples of it in action, and ways to implement it in your own work. I picked it up because I’d heard “Jobs to be Done” used all over the place and needed to be able to cut through buzzword bullshit.

The gist is the classic aphorism “People don’t want a quarter-inch drill, they want a quarter-inch hole.” Or, if you prefer business wisdom in meme form:

The value of the book might be entirely in some of the more practical advice for finding what your customer’s jobs are. I actually used some of these tools in a recent interview and I think it went over pretty well. All in all, it is a quick read (4 hours), and will probably result in your career being at least $15 more successful.

Rocket Men

by Robert Kurson

The Apollo Program is a fascinating study of organizational design. It started disastrously with Apollo 1’s fatal launchpad fire. Subsequent missions were largely uncrewed, testing components of the lunar flight system. During these early tests, the Soviet space program was advancing much faster than the American’s, putting an immense amount of pressure on NASA to deliver a propaganda victory to the US. NASA was huge, a bureaucracy of epic proportions. And when it came time to plan Apollo 8, NASA’s leaders decided to bet everything they had on a manned orbit of the moon, the first one in history.

The story of Apollo 8’s success is riveting. Kurson does a great job of telling it.

Shanzhai

by Byung-Chul Han and Philippa Hurd

Such a cool thing to read about: concepts that we take for granted like originality, authorship, and duplication are understood entirely different in East Asia. I wonder if it’s possible it is to maintain a truly global marketplace of both ideas and goods when there are some things (like art or literature) which are valued so totally differently by different people. In the west, duplicating something removes all value from the end result, whereas in China a duplicate is often more valuable than the original. Such a completely different way of understanding creativity — do you think it’s possible to adopt this viewpoint as an outsider?

The Goal

by Eliyahu M. Goldratt and Jeff Cox ★

This is one of the best business books I’ve read. Granted: I haven’t read a whole lot of business books. But this one is very good nonetheless.

It’s unorthodox: it’s written as a novel. It follows Alex Rogo, a plant manager for a fictional manufacturing conglomerate. Alex’s plant is on the brink of shutting down, and his marriage is in shambles. Through a series of discoveries and experiments, Alex turns the plant around and saves his marriage.

The ideas in the book are an outline of Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints, which is an offshoot and response to Lean Manufacturing and the Toyota Product System. If you don’t already know, I’m really into manufacturing processes; the mental technology created by Henry Ford and Taiichi Ohno have really neat applications in digital product creation. This book was a really neat way to learn about some of those tools and understand them in a real-world (hypothetical) context.

At the end of the book is a more traditional essay that walks through the history of the application of Lean Manufacturing at Hitachi, and discusses how important it is to not simply try to copy the success of other companies by copying their methodologies.

The Art of Taking Action

by Gregg Krech

This is a solid, well-organized, somewhat survey-ish collection of essays on what Zen & Buddhism & Eastern philosophy have to say about taking action, being productive in a meaningful and rewarding way. It’s easy to read in chunks (I read it over 6 months).

One of my favorite parts of the book is about using your time wisely. Specifically, when you decide to do (nor not do) something, there’s more than just your own time at stake. Key passage: “Which is longer—15 minutes of waiting for someone who is late, or 15 minutes of keeping others waiting?” That is to say, when you keep someone waiting for 15 minutes, you steal 15 minutes of their time. Apologies if I’m stealing too much of your time with this review.

Radical Candor

by Kim Malone Scott

I read this book because my current manager said it was one of her favorites. She’s a total enigma to me, so I thought reading it would give me some insight into how her brain works.

50% of this book is familiar conventional wisdom type stuff if you’re currently working (or have ever worked) in tech. Management is hard! Maybe have some 1:1s? It’s a roadmap to being a decent manager if you get parachuted into a fully-formed team at a 1k±person org.

25% of the book is good framing for what actually makes a manager effective. These parts I found rather useful. You have to actually, really, truly care about the people you manage before you can be candid with them. Compassion is not the same thing as empathy, and one of the two is far more valuable in a relationship. Sometimes it’s best to be honest with someone even if it will hurt them.

The last 25% of this book is catnip for sociopaths. I usually stick to one color for highlighting (yellow, I think this is an interesting passage) but I brought out a new color for this stuff (red, I vehemently disagree). I worry that assholes of every stripe will over-index on this material. “I regret to say that if you can’t be Radically Candid, being obnoxiously aggressive is the second best thing you can do.” Yes, this is an actual quote from this book.

Kim Scott is infuriating as a character. She name-drops constantly. (paraphrasing) “Oh, this one time my friend Andy Groves said this, which convinced me to work for Sheryl Sandberg instead of working for Larry Page.” I don’t think she ever actually spoke to Steve Jobs, but his name appears more than anyone else in the book. She nostalgically looks back on her first job, running some team at an international diamond syndicate? Weirdly, I can’t relate to that.

High Output Management

by Andrew S. Grove ★

I finally finished this after a few years of off-and-on reading. Such a solid book. I found that much of the advice was really befitting a manager-of-managers, which is a very small percentage of people in the workplace. The advice is still solid and applicable nonetheless.

Favorite part: the scorecard at the end! Such a Grove move.

Here’s one of my favorite highlights:

The idea that planners can be people apart from those implementing the plan simply does not work. Planning cannot be made a separate career but is instead a key managerial activity, one with enormous leverage through its impact on the future performance of an organization.

Several Short Sentences About Writing

by Verlyn Klinkenborg

This is a very good book about writing. Not just about the form of writing, or the action of writing. It’s also about why we write, what is so challenging about writing, and what makes good writing good.

After reading the fist half, I found it really hard to write. The book advocates for a style of writing where every single word in every single sentence has a purpose. It is extremely difficult to actually do this.

One of my favorite excerpts:

The most subversive thing you can do is to write clearly and directly, Asserting the facts as you understand them, Your perceptions as you’ve gathered them.

The Square and the Tower

by Niall Ferguson

The Square and the Tower is a history of networks. It begins with the Illuminati and ends with Trump’s election; in between, networks rise and fall in a constant churn. Ferguson combines his own original research with piles of other analyses to paint a picture of the conditions that enable networks or hierarchies to prevail.

It was a little slow getting through the early history of networks, since hierarchies easily prevail when the spread of information can be controlled. I got really into the book as it started covering the 70s in the United States. It turns out Henry Kissinger’s networks were the source of much of the diplomacy happening in that decade; Ferguson’s diagrams of these networks are really neat.

Dare to Lead

by Brené Brown

This was another book I read to try and understand my manager’s leadership style. Between this and Radical Candor, I see a pattern.

There’s some good material in Dare to Lead. The best parts delve into the research Brown has done, featuring quotes and case studies of scenarios where “brave” — emotionally-aware —leadership drove positive outcomes.

Other parts of the books are just platitudes. “Rumble with vulnerability,” “embrace the suck,” “learn to rise,” etc are cloying catchphrases, shorthand for more nuanced aspects of emotionally-aware leadership.

The similarities with Radical Candor are most apparent in what I think of as “catnip for sociopaths.” It’s ok, Brown says, to cry at work — so if you make someone cry, maybe you’re just doing a really good job at being emotionally engaged. The paradox is scary: you can cause emotional responses (good and bad) by being emotionally present yourself, or by being completely emotionally removed.

Overall, I think the book isn’t really the best way to get at mindful and compassionate leadership. But it might be worth the short read if you work with any of Brené Brown’s acolytes.

Join the mailing list

I'll send new posts to your inbox, along with links to related content and a song recommendation or two.