Design systems enable designers and developers to quickly create quality software on a massive scale. As the needs of software-driven businesses grow even larger, design systems are evolving — they are beginning to look and work like APIs.

In software development, “API” stands for “Application Programming Interface.” An API is a reliable way for two or more programs to cooperate. It allows programs to work together despite differences in hardware, language, architecture, or other operating constraints.

APIs power the internet. They are so powerful because they embody a contract: system A promises to act in a predictable way, as long as system B requests that action in an agreed-upon way. Say system A is PayPal and system B is Etsy: PayPal promises to make a transaction between two bank accounts (a buyer’s and a seller’s), as long as Etsy requests that transaction formatted in a secure and trustworthy way with permission from its users.

As long as these contracts are in place, Etsy and PayPal can write and re-write their own systems without needing to check in with each other. They can work independently and efficiently, according to their own needs. A reliable API creates trust and drives cooperation.

The API model is the perfect match for communication between designers and developers.

A Pseudo-API

If you’re a designer or developer, there’s already an API layer between you and your counterparts. That API might not be well-documented or consistent, but it forms the basis for your communication with each other.

For instance, at Bitly (where I work), designers provide information about design decisions in the form of Sketch files in a tool called Abstract. We’re working with engineers to make sure the format works for everyone as an efficient and accurate way to share specifications.

These standards and informal working agreements look a lot like the beginnings of an API. But our documentation isn’t like a typical API’s documentation (for an example of a well-documented API, see Stripe’s API reference). The design team hasn’t listed any endpoints. There are no sample requests to learn from, or expected return values to test against. Our pseudo-API doesn’t have an uptime guarantee, a service-level agreement, or rate limits. It also doesn’t fail very gracefully. When something goes wrong, no errors are thrown, and nobody’s pager goes off.

A small team can work through this uncertainty without losing much productivity. But as a team grows, it needs a clearer contract between designers and developers.

Design Systems

Design systems have become an essential tool for fast-paced application development teams. A good design system provides some of the documentation developers need in order to get information about what they are building. Like an API, a design system is an abstraction. An API abstracts some of a program’s functionality; a design system abstracts some of the design process.

Companies like Salesforce have led the way in implementing large-scale design systems. Salesforce has thousands of developers and designers working on features across many platforms and applications. To enable this kind of work at scale, the team collaborated to produce a design system called Lightning.

Lightning is a contract. On one side, it outlines very specific ways for developers to mark up their code to ensure the user experience is delivered consistently. For instance, a developer agrees that they’ll use a specific style of markup:

<button class="slds-button">Button</button>In return, Lightning guarantees that this button will have the proper appearance and functionality. It will meet Salesforce’s standards of usability and accessibility.

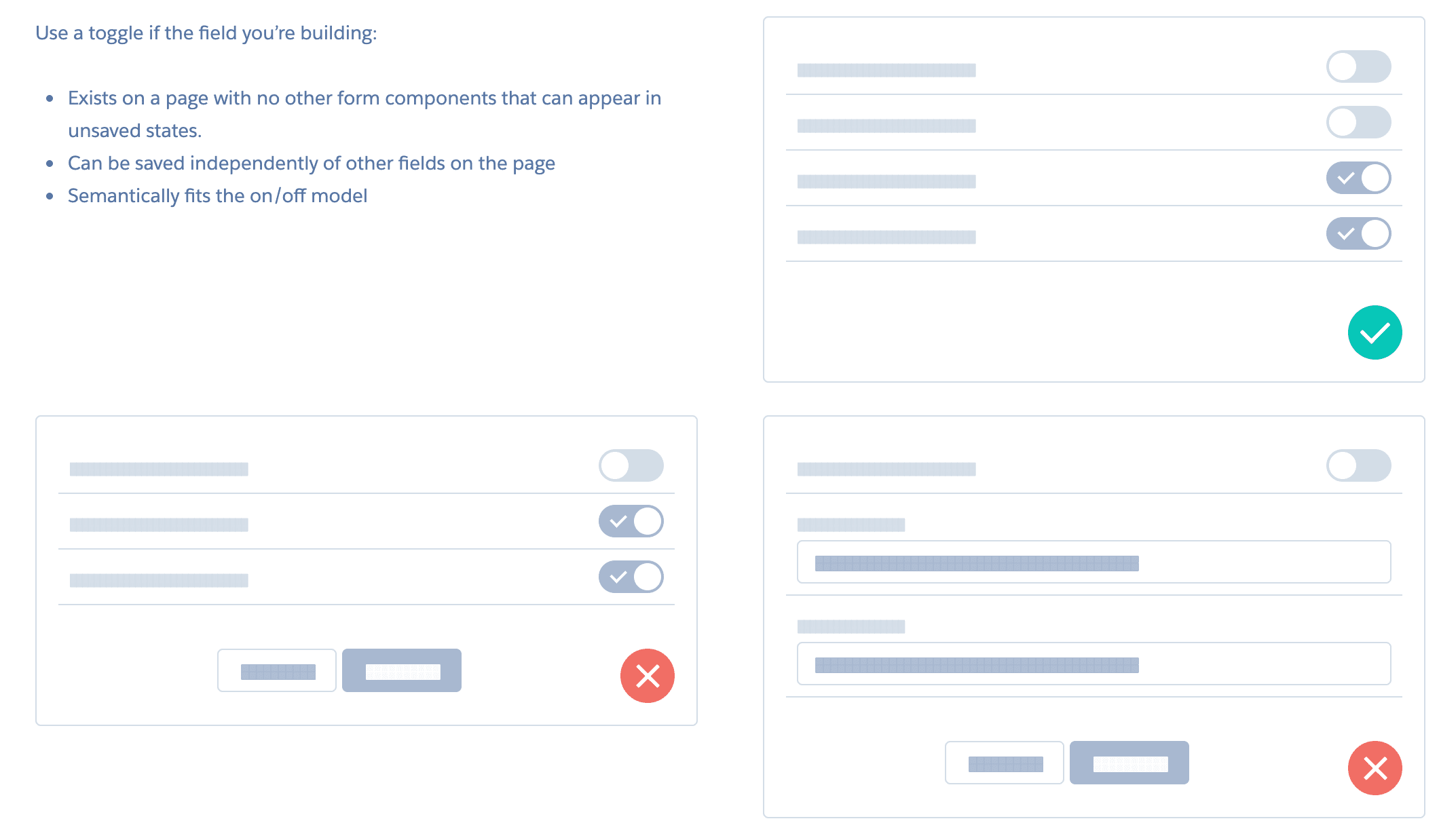

On the other side of the contract, Lightning specifies rules for creating or modifying design specifications. For instance, a designer agrees to follow guidelines for using toggle switches in forms:

In return, Lightning promises that these design decisions will be delivered quickly to end users with fidelity and integrity. The application will continue to meet Salesforce’s standards of performance and reliability.

The Problem with Design Systems as APIs

Lightning works for Salesforce, but it requires a dedicated team of engineers and designers. The design system team is solely responsible for Lightning’s continued performance: they maintain the documentation, educate users, evangelize for adoption across the organization, and monitor how the system is working.

A dedicated design system team is required because a design system is only a low-level abstraction of the design process.

This means the design system’s documentation — the website or wiki or design file that describes it — is its most useful application. For instance, the easiest way to use the colors Lightning provides is to visit the ‘Colors’ page on Lightning’s website.

Think of this like a phone book. A phone book is a low-level abstraction of a phone number directory. To find someone’s number, you flip through the pages of the phone book until you find their name. A whole team of people produces the phone book, printing and distributing it on a regular basis to ensure it is up to date.

Adding one level of abstraction to a phone directory means removing the printed book from the equation. Instead of flipping through pages, a user types a name into a search box and instantly sees that person’s phone number. The number can be kept up to date without reprinting a hefty book. Other programs can read this information, too: Integrations to messaging apps might mean the end user never needs to see the phone number at all.

Abstracting a Design System Into a Design API

What does a design API look like? Taking cues from other software APIs, a design API has four ingredients:

- Rules for making requests

- A URL called an endpoint that serves as the address for incoming requests

- A clear definition of what a properly formatted request looks like

- A clear definition of what the API’s response will be under different circumstances

Rules for Making Requests

There are many different protocols for APIs on the web, like SOAP and REST. Each protocol defines rules for how requests can be made. REST, for instance, defines the “verbs” that a request can include: “POST” adds new data, while “GET” reads existing data. Likewise, our design API needs rules to ensure a user can interact with it in predictable ways.

Additionally, some APIs require users to tie their requests to a specific account. There are many different ways of authenticating requests, from simple password-like tokens to more complicated exchanges like OAuth. Authentication helps an API protect functionality from misuse, accidental or otherwise.

A design API needs rules around what kinds of requests can be made. Is it read only, or can a user update design information via the API, too? What kind of authorization is needed for each kind of request? Defining and providing these rules to users keeps the API running smoothly.

An Endpoint

An endpoint is the URL used to make a request to an API. For example, to shorten a link with the Bitly API, you send a request to https://api-ssl.bitly.com/v4/shorten.

Our design API might have an endpoint for system colors, like https://example.com/api/colors. Or an endpoint for a dropdown component: .../components/dropdown.

Example Requests

The most basic request in an API is to simply request to see the information provided by an endpoint. For example, a design API might treat GET https://example.com/api/colors as a complete request, and respond with a list of colors.

More complicated requests involve extra information in the form of what are called query parameters. Query parameters get added to an endpoint’s URL and provide data to the API. An example of a query parameter is ?v=uwprhJZHd5Y at the end of https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uwprhJZHd5Y: the string of letters and numbers tells YouTube which video you’d like to watch.

An example request with query parameters solves a common use case: a web developer needs colors in hex format — #ffffff — while an iOS developer needs them to be formatted as a UIColor — [UIColor colorWithRed:1.00 green:1.00 blue:1.00 alpha:1.0];. Our design API could respond to the requests GET https://example.com/api/colors?format=hex and GET https://example.com/api/colors?format=uicolor with only the correctly-formatted colors.

Example Responses

Example requests give users guidelines for interacting with the API. But that’s only half of the equation: the API needs to talk back.

Consistent and well-structured responses are vital to effective APIs. For instance, if GET .../colors results in a list of hex values, you wouldn’t expect GET .../colors/blue to result in RGB values.

An example response for the GET https://example.com/api/colors action might look like this:

[

{

"name": "blue",

"value": "#0000ff"

},

{...}

]Providing this example tells a user to expect the color to be provided in hexadecimal format, along with each color’s name. A developer could use this template to write their own application, knowing that the API will always provide the information in this format.

Errors

An important but often-overlooked feature of an API is error handling. If a request to the API doesn’t result in the desired action, the API should respond with some information on what went wrong. Some common errors are:

- Not found: sent when the request was valid, but there’s nothing available at the specified endpoint.

- Server error: sent when something is wrong with the API itself.

- Authentication error: sent when authentication is required but wasn’t present in the request.

- Invalid request: sent when the user’s request wasn’t correctly formatted.

Good error handling in a design API would help the software on the other end know how to proceed. For example, sending the request GET https://example.com/api/colors/fuchsia might return a ’Not Found’ error if fuchsia isn’t a color in the system. The program that made the request might then try something more common, like GET https://example.com/api/colors/purple. If the original request resulted in a ‘Server Error’ instead, the requesting program might wait and try again later.

Putting It All Together

Combining these components, we get an example of what an API for design might look like.

How to use the API

Our API accepts form-encoded request bodies, returns JSON-encoded responses, and uses standard HTTP response codes, authentication, and verbs.

Endpoint

https://example.com/api/colorsExample request

GET https://example.com/api/colorsExample response

[

{

"name": "blue",

"value": "#0000ff"

},

{...}

]This is a very simple example of how a design API would be able to provide design information to another program.

The Current State of Design APIs

Design Tokens

Some design systems, like Lightning or Shopify’s Polaris, have pioneered the use of design tokens. Design tokens are structured values in a machine-readable file, similar to the response you’d expect from a design API.

Salesforce’s Theo and Amazon’s Style Dictionary are leading the way for the creation and distribution of design tokens. Both perform the same basic function: given a single set of design decisions, they generate a wide array of formats suitable to be used directly in a platform or application.

I recently used Style Dictionary to build a set of design tokens for Bitly. Those tokens are then distributed via NPM, enabling Bitly developers to pull in the latest version of our design decisions without needing to dig into Sketch files or ask on Slack. Design tokens are a huge step towards a fully developed design API. However, they are generated and distributed in bulk. If you only need one token, you need to import the whole library. That means they’re still a type of phone book, albeit one that is formatted in a way that software can easily read.

Also, design tokens are read-only. Updates to the original values require a completely different set of tools than downloading and using the tokens themselves. This division of labor requires more contributors, leading to the kinds of dedicated teams we see publishing and maintaining design systems today.

Standard Formats

Every design system has its own way of defining colors, font sizes, spacing, and type styles. For example, Google’s Material Design designates 14 shades of each color, using a numbered system to indicate how dark each shade is. Lightning, on the other hand, uses aliases like $brand-text-link or $color-background to denote how each color should be used. In “Interoperability," Brent Jackson describes how this makes software development — specifically, moving from Basscss to Tachyons, both of which are CSS libraries — more difficult:

The real tragedy here in the divergent naming conventions is that if you’ve started building an application with Basscss, but then want to upgrade to something more fully-featured like Tachyons, you’ll have to do a lot of manual work to migrate. Essentially, HTML templates written with either of these libraries isn’t as portable as if we’d used a standard syntax, for example inline styles.

Jackson goes on to suggest a standard format for colors, fonts, and sizes.

The emergence of standard formats means that applications can work seamlessly with multiple design systems or migrate from one to another with little effort. Standardization also makes it faster to build new systems. Having a comprehensive template for your design language all but eliminates one of the hardest problems in software development: naming.

But an API also reduces the importance of a consistent naming scheme. A well-documented and machine-readable format for design data can be easily transformed into whichever format your application requires.

The Future of Design APIs

The increasing popularity of design tokens and the drive towards a standard format for design systems mean that design APIs are just around the corner. These rich APIs will enable what I call networked design systems.

Networked design systems are sets of applications and tools that are capable of communicating with each other about design decisions. Contrast this with the state of the art: the closest we come to networked tools are libraries like AirBnB’s react-sketchapp, which is capable of importing components from an application’s codebase into Sketch. This connection enables designers to use up-to-date components directly from AirBnB’s applications. But it’s a one-way connection; designers can’t push changes back to the components.

New applications like Modulz promise to go a step further, empowering designers to work directly with application code in a visual medium. Modulz is a part of the “no-code” revolution, a drive to put more of the software creation process directly in the hands of designers, business analysts, product managers, and executives. Design APIs will be crucial to these tools. Instead of a developer updating the CSS, HTML, and JavaScript to reflect the latest design decisions, the design API serves as the connection between a designer (or, heaven help us, a stakeholder or client) and the finished product.

Such a direct connection opens up entirely new ways of building software. Today, design decisions like colors, font sizes, and spacing are ‘baked’ into an application’s code. A developer writes design specifications into the source code, which is then compiled and delivered to an end user. This causes problems when many developers are working on an application: different parts of the codebase are updated at different times, while different design specifications are baked in. The more features an app has, the harder it is to maintain a consistent user experience.

A design API would allow an application’s compiler to request the latest specifications every time it runs, ensuring the result is always up to date. Developers no longer have to bake design decisions into their code. No matter how large the code base, all the design decisions are maintained in a single place and distributed when needed.

Keeping design decisions separated from your application’s code base has another advantage: you can build logic into the API without adding to the complexity of the app itself. By logic, I mean programs that concern the design decisions themselves. These programs can run automatically or at a user’s request via an API endpoint. Accessibility tests could run every night, providing valuable usage guidelines to users who want to adhere to web standards like WCAG. These tests could also run when a user adds a new color or updates an existing one, and the API could reject the request if the new color doesn’t meet accessibility standards.

Conclusion

APIs are a powerful paradigm. Using the groundwork laid by the pioneers of networked programs, designers and developers can evolve their approach and unlock new ways of collaborating. And yet, design APIs don’t seem like a stretch of the imagination. An API-driven approach is the natural extension of the work currently being done on design systems, including tokens and standardization projects.

That’s why I’m so excited about design API-driven tools and frameworks: A fully-networked design system, powered by a design API, gives massive leverage to even the smallest teams. Using a design API, designers and developers can maintain larger and larger codebases, deployed over multiple apps and platforms, without sacrificing quality or consistency. Design concerns like accessibility could be automated and managed by dedicated systems; changes could be tested on the fly, in production, by a single designer.

As design systems evolve into fully-featured design APIs, the future of design is bright.

Join the mailing list

I'll send new posts to your inbox, along with links to related content and a song recommendation or two.