At a time when data is king, product designers should place more trust in their intuition.

Recently I attended Front, a product management conference in Salt Lake City. There, Maggie Crowley, product manager for a company called Drift, presented a case study in redesigning a complex feature: the chatbot builder. It helped users build their own interactive chatbots without coding or design. The team had been iterating on the design of the chatbot builder for a while, but thought it could be greatly improved by a substantial overhaul. Here’s how she recounts the process of getting buy-in from her stakeholders:

We had a feeling we could make our builder better. And you can’t really say “I have a feeling.” No one’s gonna listen to you. So like every good product manager, I tried to find some data … But unfortunately, I didn’t see anything. Our metrics looked perfectly fine.

Lacking data, Maggie and her team interviewed users, gathering anecdotes and qualitative insights. They used this research to get the permission needed to redesign the chatbot builder. When they launched, their users were ecstatic. One called the improvements “life-changing.”

At the end of the talk, an audience member asked “How did you know your redesign was better?” Maggie’s response surprised me:

It came down to a feeling. It was just so stupidly obvious that we needed to make that change.

Maggie’s story perfectly captures the modern expectation that data drives decision-making. And if Maggie had let that expectation dictate her decision, her team wouldn’t have improved the product. The difference between success and the status quo started with a feeling.

I can relate to Maggie: my stakeholders expect data to compel every design decision I make. Even when the decision is “so stupidly obvious,” we gather data. But our insistence on data-driven design holds us back. It slows down iterations and limits innovation.

Instead of relying on data to guide our decisions, we should be more willing to follow our gut.

The data dilemma

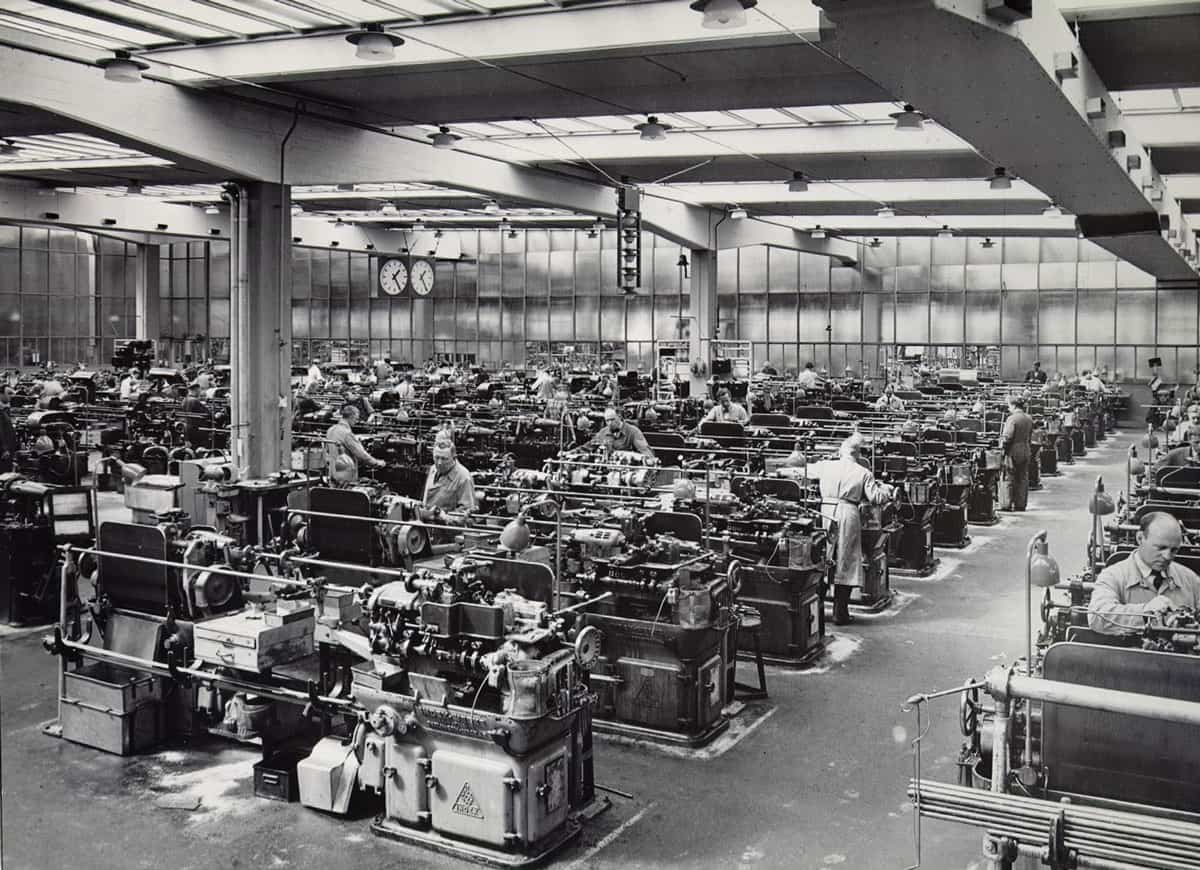

Data-driven design is not a new concept. Its origins can be traced back to the late 19th century, with the rise of scientific management. Since Fredrick Taylor first used scientific methods to maximize steelworkers’ productivity in 1882, data has been vital to business.

In 2014, Walter Frick summed it up in the Harvard Business Review:

Not a week goes by without us publishing something here at HBR about the value of data in business. Big data, small data, internal, external, experimental, observational — everywhere we look, information is being captured, quantified, and used to make business decisions.

Data brings a feeling of objectivity to decisions. It settles disputes. Data can demystify the past and predict the future. As Wall Street’s quantitative analysts know, the right data in the right hands can make fortunes. But the wrong data, even in the right hands, can be disastrous. And with data it’s hard to tell right from wrong.

For example: We’re in the middle of what scientists call the reproducibility crisis. Psychologists, clinical researchers, economists, and other data-centric academics have discovered that historic standards for proof aren’t rigorous enough. Findings that were once seen as conclusive are now regarded with doubt1. While it’s unlikely that we’ll have to rewrite everything we know about the world, the replicability crisis tells us that even data can lead us to the wrong conclusions.

The case for intuition

If you design — or code, or write strategy, or make decisions of any kind — you probably have some kind of intuition about the work you do. Depending on how much experience you have, that intuition might just be a tiny whisper in a noisy room. But you should still listen to it.

In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman references Herbert Simon:

The psychology of accurate intuition involves no magic. Perhaps the best short statement of it is by the great Herbert Simon, who studied chess masters and showed that after thousands of hours of practice they come to see the pieces on the board differently from the rest of us. You can feel Simon’s impatience with the mythologizing of expert intuition when he writes: “The situation has provided a cue; this cue has given the expert access to information stored in memory, and the information provides the answer. Intuition is nothing more and nothing less than recognition.”

Put another way, intuition is a hint that helps us navigate problems based on experience; it’s a compass needle wiggling towards the north pole. This kind of effortless thinking is what Kahneman calls “System 1” thinking. System 1 operates “automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.” Even when System 1 is biased (and it often is), it’s a useful tool in decision-making.

When to trust your gut

When making a decision, you’ll likely have some intuition about the potential outcome. You’ll have to decide whether or not to gather data to guide your decision-making. Those are the two possible starting points: either you gather data or you don’t. And then there are two outcomes: either you’re right or you’re wrong.

The four possible scenarios are:

- Trust your intuition → your decision is wrong

- Gather data → your decision is wrong

- Trust your intuition → your decision is right

- Gather data → your decision is right

There are lots of variables at play, too. Gathering data is an additional step, and comes at some cost (c), whether it’s in real expense or in the cost of delaying your decision. And while there’s a chance your intuition is right (pi), it’s worth considering the likelihood that your data leads you to the correct decision (pd). Finally, the value of the decision (v) is important: it can be almost negligible (what color should our company T-shirts be?) or career-defining (at what price should we set our IPO?).

We can put all these variables into an equation:

If the result of this equation is a positive number, follow your intuition. If the result is a negative number, gather data before deciding. Use the calculator below to experiment with different variables to see how they impact the value of intuition.

Of course, you can’t know the exact chance that your intuition is right, or how likely the data is to be right. But just by estimating the difference — that is, how much more confidence you gain by gathering data — you can get a good sense of whether you should go with your gut.

A real-world application

Let’s revisit Maggie’s decision to redesign Drift’s chatbot builder. The cost of gathering data was high since the team would be starting from scratch. The change was “stupidly obvious,” meaning there was a very small difference between an intuition-based approach and a data-based one. The value of the decision was substantial: a successful redesign would mean a real increase in engagement. Here’s what that looks like:

- Very small difference in likelihood of being correct between intuition and data (pi ≈ pd)

- High decision value

- High cost of gathering data

Because the large positive cost of gathering data outweighs the small product of the first two terms, Maggie was right to go with her gut.

So when should you trust your intuition?

- When gathering data won’t greatly increase your odds of being right, and

- When your decision doesn’t high stakes, and

- When the cost of gathering data is high.

It can be hard to know when these conditions are present. But when you can identify them, trust your intuition.

Join the mailing list

I'll send new posts to your inbox, along with links to related content and a song recommendation or two.