There is a disconnect between product design and product engineering.

Three factors contribute to this disconnect:

- Products get shipped faster every day. DevOps teams automate huge amounts of the delivery process, enabling engineering teams to ship code many times every day.

- Designers have access to more information than ever before. UX research, product analytics, and tight-knit product teams provide torrents of data. Designers are always learning, and their designs evolve to reflect their understanding.

- Implementing a design hasn’t changed much. The design implementation process hasn’t changed much since the days of slicing PSDs. Design systems are beginning to automate some of the work, but turning mockups into code is slow. Waterfall (or other forms of one-step-at-a-time development) is still the standard practice for this transition.

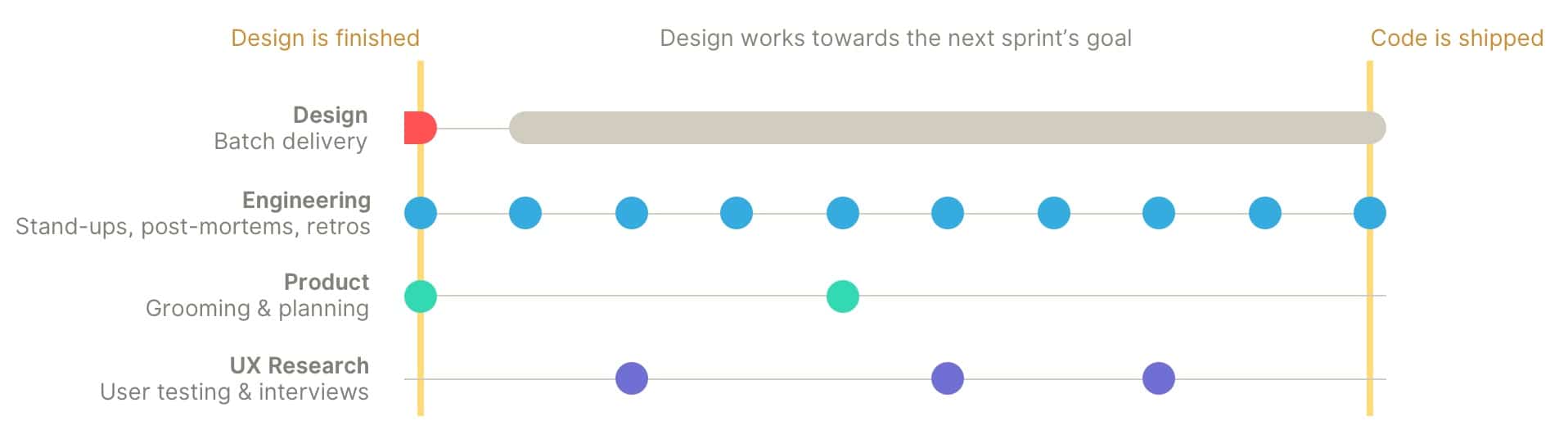

In response to this disconnect, designers are often working at least one sprint ahead of engineers. While one sprint might not seem like much of a lag, a typical product team learns a lot after the design hand-off.

After seeing the final designs:

- The engineering team discusses the work every day in stand-ups.

- The product team provides feedback and refines metrics and goals.

- UX research shares insights into user’s real-world experience.

To stay one sprint ahead, design can’t deliver on this knowledge until the next sprint. It all starts to be reminiscent of the “Pre-taped Call-in Show” from Mr. Show.

Instead of working ahead, we should finish designing as close to the end of a sprint as possible: just-in-time design.

Just-in-time manufacturing

Just-in-time design takes its name from Just-in-time manufacturing (abbreviated JIT). JIT is a way of moving materials through a production process in which each step starts as soon as the necessary components arrive. Parts continue down the line only when needed. Extra inventory is wasteful, and workers put an extreme focus on quality.

JIT originated in Japan to maximize the output of a small amount of factories and resources. Along with then-novel practices like kanban and kaizen, JIT helped Japan rebuild their industrial manufacturing capacity after World War II. This method has gone on to influence American companies like Dell, Harley Davidson, and General Electric.

We can apply JIT to design by following some of the key principles outlined by Mehran Sepehri in Just in Time, Not Just in Japan.

Housekeeping: physical organization and discipline

Invest in a design system. Organized and reusable design elements benefits just-in-time design in two ways:

- Breaking designs down into independent components makes it easier to ship in smaller increments.

- A shared set of design tools enables engineers to ship faster and opens the way to automation.

Lot sizes of one: the ultimate lot size and flexibility

Ship in the smallest increment possible. The “lot size” in manufacturing refers to the number of parts that get delivered as a group. For just-in-time design, delivering in smaller batches make it much easier to see the impact of each change.

Delivering in smaller increments also makes the feedback loops more forgiving. If one design doesn’t achieve the desired outcome, the next design is adjusted and improved.

Faster feedback cycles provide real-world insights on a regular basis. For instance, if a big redesign takes 6 months and only shipped when it’s 100% ready, the team is waiting 6 months to find out if their designs were effective. If the team breaks the work into 6 parts and delivers one part a month, they learn much sooner if their designs are effective and can adjust as they go.

Streamlining movements: smoothing materials handling

Get embedded in the team. Designers should use sprint planning, grooming, standup, and retro as opportunities to provide design to — and recieve feedback from — the rest of the team. Designs can take the form of written or verbal descriptions, not just wireframes and high-fidelity mockups.

Use a handoff tool. Tools like Zeplin, Abstract, or Invision Inspect make it much easier for designs to flow from designers to engineers — no matter what Dan Mall says.

Pull system — signal [kanban] replenishment/resupply systems.

Only design what’s needed. Use constant communication between engineering and product partners to understand what your collaborators will need next. Then, plan on delivering only what is needed, and nothing more. Use the agile process — grooming, planning, and retro — to find any shortfalls or excesses.

Avoid creating a backlog of designs. Designs don’t age well. In the time between finishing design and shipping code, it’s likely that you’ll learn something new that changes your understanding. If you’re producing more design than can be implemented, focus more on the quality of each design.

Conclusion

The disconnect between designers and engineers is a common source of frustration in any product-focused company.

Continuously delivering small iterations based on the team’s needs can transform the product development process. This approach shifts the focus away from highly-produced, out-of-date, difficult-to-maintain design, opening up the process to tighter collaboration and a higher standard of quality.

Special thanks to Dan Alcalde and Adelle Charles for contributing to this essay.

Join the mailing list

I'll send new posts to your inbox, along with links to related content and a song recommendation or two.