Care ethics is closely related to the rise of feminist voices in philosophy starting in the 1970s. Writers at the time were inspired by the vanguard of feminism — Mary Astell in 1694, Mary Wollstonecraft in 1792, and Harriet Taylor Mill in 1869. They pointed out the dominance of men in the history of ethics and sought to understand the impact that such a one-sided approach might have on ethical theories. Care ethics emerged as the counterpoint to consequentialism and deontology. It emphasizes relationships — not tabulated outcomes or logical rulebooks — as the primary test of ethical behavior.

A note from the author

Before I dive into the history and practice of care ethics, I should address a few things.

I’m a white, cisgender, heterosexual male living in a country and a community that provide people like me significant privilege at the exclusion of others. I was conflicted about writing an essay on feminist ethics. I asked friends: is it right for me to try? Can I faithfully represent the beliefs of people who have experienced kinds of oppression and exclusion that I’ll never know?

I have good friends. They encouraged me to give it my all.

So, a disclaimer: This essay is my honest attempt at highlighting the ethical frameworks first stated by women in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. I hope I do their ideas justice. If you’re interested in learning more about care ethics, please read the original texts; I’ll provide links in the footnotes.

What is care ethics?

Care ethics puts relationships at the center of ethical decision making. And relationships are built on care: relationships with distant strangers might consist of a general concern, whereas relationships with your family and friends might involve much more direct care-giving and care-receiving.

According to supporters of care ethics, care is universal: no matter what culture or community you belong to, you experience care. This fact makes care a great foundation for ethics.

The ultimate test of ethical behavior, then, is how that behavior expresses care. We can be selfish, only caring for ourselves. We can be selfless, only caring for others. According to care theory, ethical behavior strikes a balance between selfishness and selflessness. This is “moral maturity, wherein the needs of both self and other are understood.”1

A history of care ethics

While the label “feminist ethics” didn’t appear until the 1970s, there is a rich history of women calling out the gender-specific flaws of philosophy. For example, Mary Astell’s 1694 book A Serious Proposal to the Ladies and its 1967 sequel call out “those deep background philosophical and theological assumptions which deny women the capacity for improvement of the mind.”2 In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Mary Wollstonecraft criticized the contemporary interpretation of virtue ethics — that ethics applied differently to men and women: “I here throw down my gauntlet, and deny the existence of sexual virtues.” She continues, “women, I allow, may have different duties to fulfill; but they are human duties, and the principles that should regulate the discharge of them … must be the same”3

In the 1980s, two authors picked up Wollstonecraft’s mantle and crafted complementary theories of ethics.

Carol Gilligan and gender

Carol Gilligan, in her landmark 1982 work In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development, illustrated gender biases in the works of Lawrence Kohlberg by revisiting one of Kohlberg’s studies, the “Heinz dilemma.” Kohlberg’s study focused on two eleven-year-old children, Jake and Amy.

In the Heinz dilemma, the children are asked whether a man (“Heinz”) should steal an overpriced drug to save his wife’s life. Jake sees the Heinz dilemma as a math problem: the right to life is greater than the right to property. Jake reasons that Heinz ought to steal the drug. Amy disagrees, believing Heinz shouldn’t steal the drug. If Heinz is caught and goes to prison, she explains, his wife will be even worse off. Amy sees the dilemma as a narrative of relationships, not as a logic puzzle.4

Kohlberg concluded that Jake is further along in his moral development than Amy. Gilligan, a fellow researcher in the study, sharply criticized this view:

While current theory brightly illuminates the line and the logic of the boy’s thought, it casts scant light on that of the girl. The choice of a girl whose moral judgments elude existing categories of developmental assessment is meant to highlight the issue of interpretation rather than to exemplify sex differences per se. Adding a new line of interpretation, based on the imagery of the girl’s thought, makes it possible not only to see development where previously development was not discerned but also to consider differences in the understanding of relationships without scaling these differences from better to worse.5

Gilligan concluded that a new understanding of moral development was needed.

Nel Noddings and care

In 1984, Nel Noddings published Caring; it was the kind of framework that Gilligan called for. In Caring, Noddings defined relationships as having two fundamental roles: the “one-caring” and the “cared-for.” Ethical action, she claimed, comes from two intertwined motives: our natural inclination to care for others, and our memories of being cared for.

One of the central themes of Caring is what Noddings called “engrossment.” To be engrossed in caring means taking an active interest in the needs of another. Noddings specified that engrossment doesn’t have to be “intensive [or] pervasive in the life of the one-caring,” but “it must occur.”6

To Noddings, behaving ethically requires being engrossed in the needs of others and caring for them. She describes ethical caring as happening when you care out of a sense of duty or obligation, not just out of convenience or self-interest. Therefore, immoral behavior happens when you fail to meet your obligations. “[When] one intentionally rejects the impulse to care and deliberately turns her back on the ethical, she is evil, and this evil cannot be redeemed.”7

How to apply care ethics

In order to see design through the lens of care ethics, you have to first identify the relationships that exist in design.

First, there’s the relationship between the person doing the design and the person consuming the design — for digital products, we call these consumers users. The best way to understand the relationship between maker and consumer is through user research.

Qualitative User Research

Once a given, the value of user research has recently been called into question by today’s growth-hungry startup culture. On one hand, being smarter about what you build can give your company a competitive advantage. On the other hand, user research can take time, money, and energy.

Uber made its stance on user research known in 2019 when it laid off 800 employees, including almost half its research team.8 The Washington Post reported:

Executives inside Uber have told employees they will devote fewer costly resources to user experience and research — including teams who worked on those issues — and conduct more direct testing of in-app features for riders and drivers.

“We will deliberately rely less on user research for tactical features and instead rely more on experimentation,” Uber’s chief of product, Manik Gupta, wrote to employees in an email the day of this month’s layoffs. “We will focus on fewer projects with more direct business impact.”9

It’s debatable whether or not user research is the best way to assess the direct business impact of incremental product changes. But no amount of A/B testing will make an acceptable substitute for empathy.

As Erika Hall put it in Just Enough Research:

You do user research to identify patterns and develop empathy. From a designer’s perspective, empathy is the most useful communicable condition: you get it from interacting with the people you’re designing for.10

Empathy is another way to think about Noddings’ concept of engrossment; empathizing with your users corresponds to having an active interest in their needs.

User research studies don’t need to be lengthy, complex affairs. Jakob Nielsen and Tom Landauer showed that running a test with five users over three iterations will identify nearly 100% of usability issues.11 But that’s only the business case: going beyond the original research, I believe that talking to your users creates a lasting interest in their well-being.

Ethical community building

Ties between designer and user aren’t the only relationships to consider. It’s possible — likely, even — that your work facilitates relationships between other people. If we want to design against the backdrop of care ethics, we have to understand those relationships.

An example: if you host a design conference, you are facilitating relationships between the conference’s attendees, speakers, vendors, and staff. To fulfill your obligation to care for those people — and to increase the likelihood they’ll care for each other — you need a code of conduct.

Ashe Dryden, a diversity advocate whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Scientific American, Wired, and on NPR, makes the case for a code of conduct:

The people most affected by harassing or assaulting behavior tend to be in the minority and are less likely to be visible. As high-profile members of our communities, setting the tone for the event up front is important. Having visible people of authority advocate for a safe space for them goes a long way.12

If you’re writing your own code of conduct, a great place to start is this template for conference organizers, originally written by the organizers of JSConf.

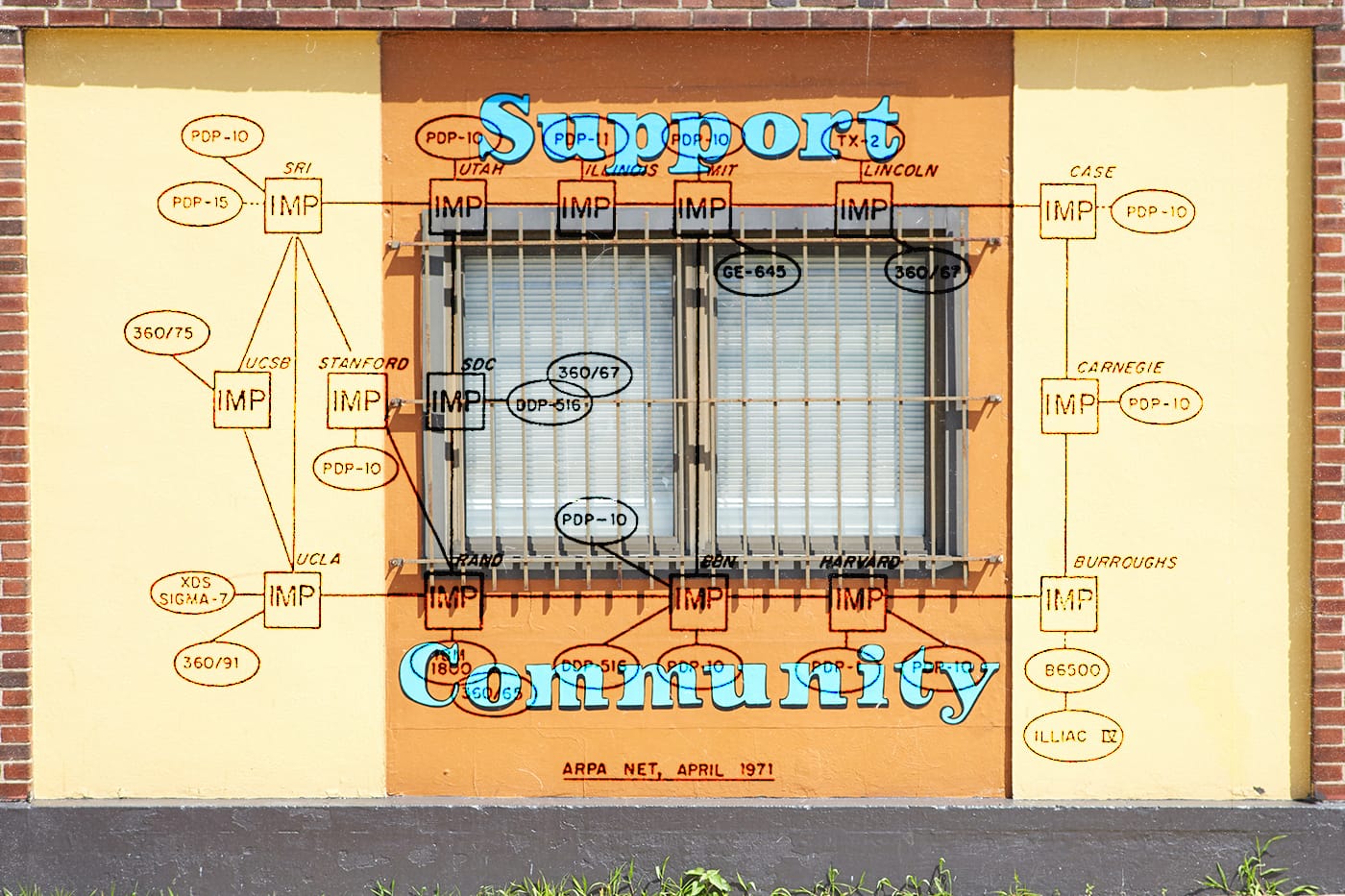

Communities aren’t always bound by a physical space, a limited time, or a single topic. Online, communities can spread out in every direction, connecting people across physical and socioeconomic chasms. The designers of community platforms must scale their efforts to match the growth of their user base.

This code of conduct template for online communities was written by Coraline Ada Ehmke; use it to create more ethical relationships between members of your community.

Criticism of care ethics

As a modern ethical framework, commentary on care ethics reflects the multitude of perspectives in modern philosophy. Some critics — like Vanessa Siddle Walker and John Snarey — ask about intersectionality: how much of care ethics is reflected in the identities of white women like Gilligan and Noddings? How does care ethics work for people of different ages, races, genders, sexual orientations, disabilities, or classes?13

Care ethics also stops short of identifying specific actions that an ethical person should perform. Nel Noddings identifies an obligation to care for others — how similar is this to the obligations that Kant and other deontologists talked about? And if care ethics has no litmus test for ethical behavior, how is it that different from Aristotle’s virtue ethics?

You can see how theories of ethics can blend seamlessly into one another. It’s hard to see where one ends and the other begins.

Conclusion

Until recently, the history of philosophy has been written almost entirely by men. To move forward, we have to face a hard reality: we missed something. The threads of bias have already been sewn into the fabric of academic philosophy.

Care ethics is one attempt to untangle the gendered past of moral philosophy. It puts relationships at the center of ethics: whether or not you are acting ethically depends entirely on whether or not you’ve upheld your duty to care for others.

This is a powerful way to look at design. How well have we cared for the people that use our products? How have we enabled them to care for each other? The answers to these questions point the way to a more just, more equitable, more kind future.

Join the mailing list

I'll send new posts to your inbox, along with links to related content and a song recommendation or two.

Craig P. Dunn and Brian K. Burton, “Ethics of Care,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed February 1, 2020: https://www.britannica.com/topic/ethics-of-care. ↩︎

Mary Astell, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies (Peterborough, Canada: Broadview Press, 2002). ↩︎

Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, edited by Carol H. Poston (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1988). ↩︎

Maureen Sander-Staudt, “Care Ethics,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed February 1, 2020: https://www.iep.utm.edu/care-eth/. ↩︎

Carol Gilligan, In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development, reprint edition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016). ↩︎

Nel Noddings, Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics & Moral Education, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Elsa Ho, “Five Things UX Researchers Can Do Differently: A Reflection After Uber’s Lay-Off,” accessed February 3, 2020: https://medium.com/@elsaho/five-things-ux-researchers-can-do-differently-a-reflection-after-ubers-lay-off-9dd967148056. ↩︎

Faiz Siddiqui, “Inside the New Uber: Weak Coffee, Vanishing Perks and Fast-Deflating Morale,” accessed February 3, 2020: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/09/30/inside-new-uber-weak-coffee-vanishing-perks-fast-deflating-morale/. ↩︎

Erika Hall, Just Enough Research (New York City: A Book Apart, 2013). ↩︎

Jakob Nielsen and Thomas K. Landauer: “A mathematical model of the finding of usability problems,” Proceedings of ACM INTERCHI ’93 Conference (Amsterdam, The Netherlands, April 24–29, 1993), pp. 206–213. ↩︎

Ashe Dryden, “Codes of Conduct 101 + FAQ,” Ashe Dryden & Programming Diversity, accessed February 3, 2020: https://www.ashedryden.com/blog/codes-of-conduct-101-faq#coc101why. ↩︎

Vanessa S. Walker and John R. Snarey, Race-ing Moral Formation: African American Perspectives on Care and Justice (New York: Teachers College Press, 2004). ↩︎