Let’s talk about Luddites. The actual, real, historical Luddites.

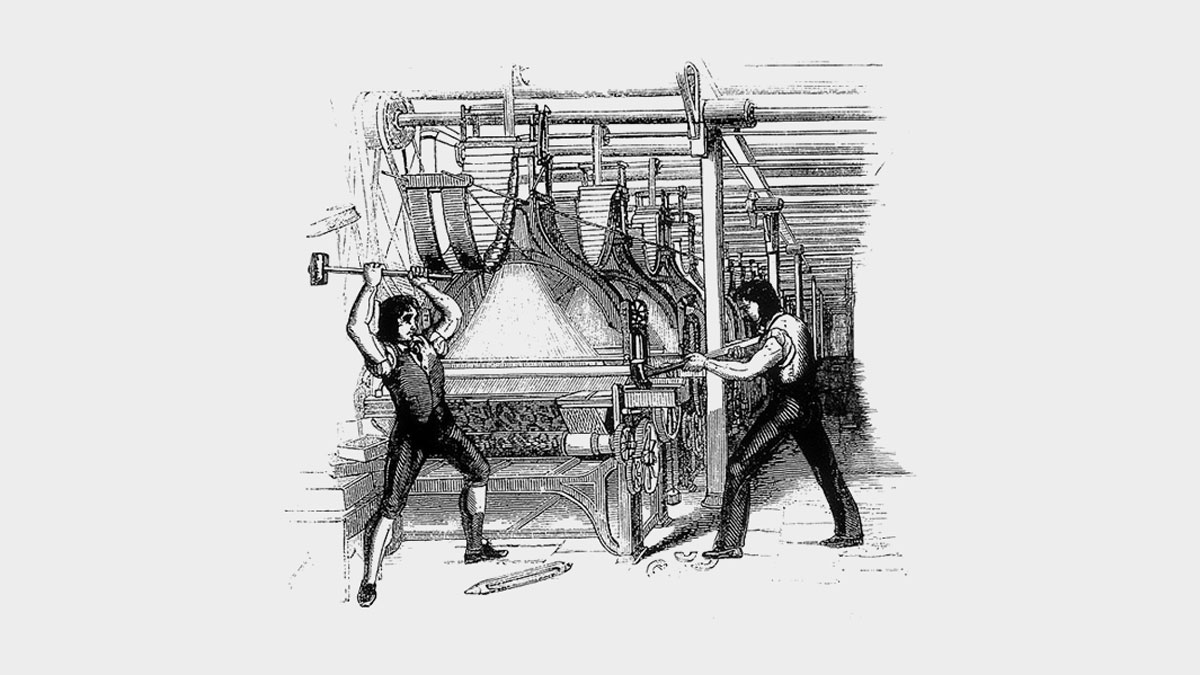

“Luddite” was the label given to a group of English workers’ rights activists in the early 19th century. They owe their name to a man who may never have existed — Ned Ludd. The Luddites were working-class people and artisans. They were reacting to the wave of industrialization that was gathering strength and threatening to overwhelm their way of life; they saw their wages decreasing and their working conditions worsening and they were compelled to pick up pistols and pickaxes and let their countrymen know what was at stake. They chose their targets carefully. Businesses that supported their workers were spared. Businesses that indiscriminately replaced skilled artisans with automated machines were burned to the ground.1

Somewhere between then and now “luddite” has become a catchall insult for anyone who irrationally fears new technology. But the capital-L Luddites weren’t irrational, and they didn’t fear technology. They resisted the way technology was used by the bankers and factory owners to increase profit margins to the detriment of skilled laborers.

Design is having a Luddite moment.

I’ve been reading (with great joy and keen interest) a sequence of blog posts by Frank Chimero, Jeremy Keith, Dave Rupert, and Brad Frost. Frank’s essay makes the distinction between gardening and architecture; the former fosters uncertainty to enable surprise, the latter reduces uncertainty to provide predictability. Frank puts modern knowledge work in the “architecture” column — I think he’d include product design as knowledge work.

Jeremy responds, lamenting design systems’ role in the architecturalization of design. The reduction of uncertainty, he says, is in the spirit of efficiency and automation. Why are we so eager to automate away our jobs?

The usual response to this is the one given to other examples of automation: you’ll be free to spend your time in a more meaningful way. With a design system in place, you’ll be freed from the drudgery of manual labour. Instead, you can spend your time doing more important work … like maintaining the design system.

Dave picks up this thread:

This kills me, but it’s true. We’ve industrialized design and are relegated to squeezing efficiencies out of it through our design systems. All CSS changes must now have a business value and user story ticket attached to it. We operate more like Taylor and his stopwatch and Gantt and his charts, maximizing effort and impact rather than focusing on the human aspects of product development.

Brad continues, expanding the discussion to include agile software development:

If we want to talk about dehumanizing digital work, look no further than Agile. Red lines! Burn rates! Story points! Requirements! Acceptance criteria!

And later:

In these structures, people are stripped of their humanity as they’re fed into the machine. It becomes “a developer resource is needed” rather than “Oh, Samantha would be a great fit for this project.” And the effect of all this on individuals is depressing.

Frank, Jeremy, Dave, and Brad are doing an important job: questioning the tradeoffs we make when we automate our work. What do we stand to gain by participating, as Jeremy says, “in the creation of [our] mechanical successors”?

Back to the original Luddites. In 1812, the British military cracked down on the vandalism and violence perpetrated by the movement. Lord Byron, romantic hero and prominent defender of the Luddites, protested the show of force:

I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces of Turkey; but never, under the most despotic of infidel governments, did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return, in the very heart of a Christian country2

A show trial of more than 60 men followed. Most were acquitted, but a few of the group’s leaders were convicted, deported, and even executed .3 Lord Byron continued to oppose restrictions on labor protests, but the Luddites soon disappeared into history.

In 1815, Lord Byron had a daughter named Ada. As a teenager, Ada became friends with mathematician Charles Babbage. She went on to apply Babbage’s ideas in one of the most consequential discoveries of the past millennium:

When she saw some mechanical looms that used punched cards to direct the weaving of beautiful patterns, it reminded her of how Babbage’s engine used punched cards to make calculations, and she developed the historic insight that a calculator could be instructed to handle not just numbers but anything that could be notated in logical symbols, such as music or words or graphics or textile patterns. In other words, she envisioned the modern computer. She also drew up a step-by-step sequence of operations for programming Babbage’s engine to generate a complex series known as Bernoulli numbers. It included subroutines, recursive loops, and a table showing how it would feed into the computer, all of which would be familiar to any C++ coder today. It became the first published software program, earning Ada the title of “the world’s first computer programmer.”4

The first software program was written by Ada Lovelace, daughter of Lord Byron, one of the Luddite’s most public advocates. The very jacquard looms that the Luddites fought to destroy were the forerunner to all modern computers.

Design systems are used by greedy software companies to fatten their bottom line. UI kits replace skilled designers with cheap commoditized labor.

Agile practices pressure teams to deliver more and faster. Scrum underscores soulless feature factories that suck the joy from the craft of software development.

But progress requires more than breaking looms.

We can create ethical systems based in detailed user research. We can insist on environmental impact statements, diversity and inclusion initiatives, and human rights reports. We can write design principles, document dark patterns, and educate our colleagues about accessibility.

We can pull the weeds at the edges of our systems and feed the roots of our core beliefs.

And ultimately, somewhere in the mess of modern product design, someone will write the first software program. Someone will invent the first computer.

Design’s Ada Lovelace is probably looking at a design system right now.

Join the mailing list

I'll send new posts to your inbox, along with links to related content and a song recommendation or two.